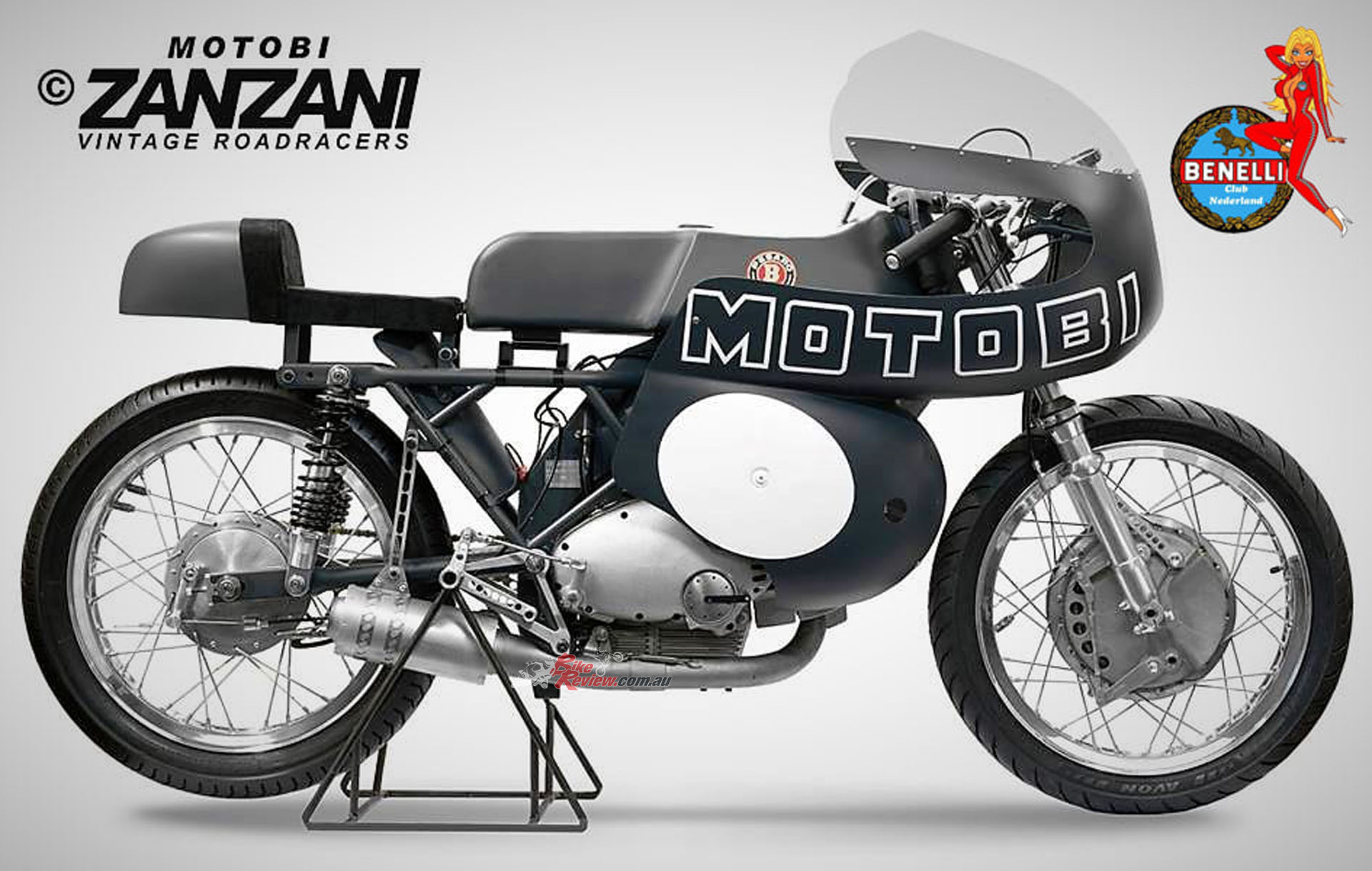

MotoBi, a forgotten Italian marque born out of a family squabble that caused Giuseppe Benelli to set up his own brand across the road from his other Brothers in Pesaro. We have the full history...

Even by the standards of Italy’s etceterini array of little-known marques back in the 1950s, MotoBi is an obscure subplot to the ongoing soap opera that the ever-changing panorama of Italian motorcycling represents. We take a look back at this forgotten brand!

Characteristically, MotoBi only ever existed because of a family squabble which saw Giuseppe Benelli, eldest of the six brothers whose mother Teresa had set them up in a mechanical repair workshop back in 1911 as a prelude to attaching the Benelli badge to their own range of motorcycles from 1921 onwards, walk out of the family factory in 1948 and cross the street to found his own rival marque.

Read Cathcart’s Racer Test on the MotoBi Sei Tiranti 250 here…

Their products were at first merely identified by a large letter ‘B’ on the fuel tank – nothing else. For over a decade the two companies co-existed in barely suppressed enmity in the city of Pesaro on Italy’s Adriatic Coast, later home of such sporting names as Morbidelli, MBA, Sanvenero and more recently the Benelli QJ marque, now under the control of China’s Qianjiang. But Giuseppe Benelli passed away in 1957 aged 78, leaving his sons Marco and Luigi to grapple with the task of keeping the firm afloat in the wake of the birth of the Fiat 500 car, which had brought the postwar boom in Italian motorcycling to such an abrupt end.

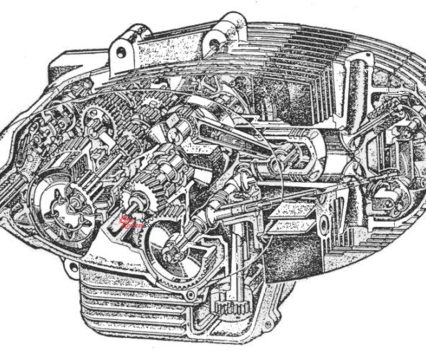

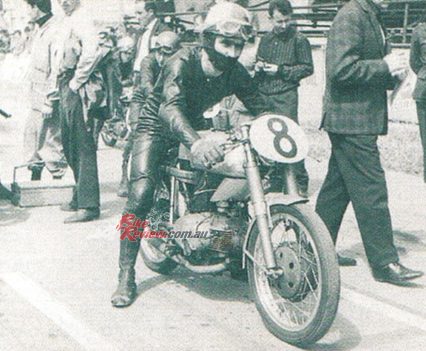

MotoBi (as it was known from the mid-’50s onwards) had carved itself a good slice of that era’s booming Italian bike market, with a range of innovative models. Initially, these were all two-strokes, including from 1953 onwards a 200cc rotary-valve parallel-twin bearing the curious name of the B200 Spring Lasting, whose pressed-steel frame and egg-shaped engine with its finned horizontal cylinders and vertical downdraught carbs, established the trademark format of future MotoBi products.

Read our history of Benelli article here…

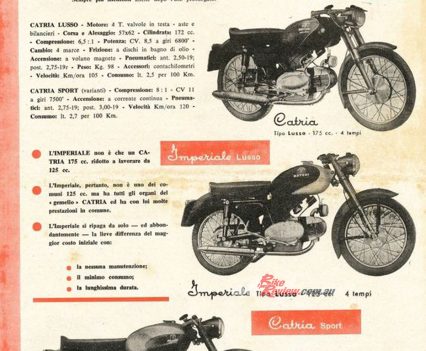

Late 1955 saw its first four-stroke models appear, a 125/175cc OHV duo bearing the Catria name and designed by freelance engineer Piero Prampolini, whose later credits included the 350/500GP four-cylinder Benellis which Jarno Saarinen took to victory on their ’72 debut, and the Benelli 650 Tornado, a late-‘60s Italian idea of what a British OHV parallel-twin should have been, but never was. Interestingly, the Catria’s horizontal-cylinder engine layout preceded by one year the later arrival of the similar-format 175cc Aermacchi Chimera, which duly morphed into the Harley-Davidson Sprint.

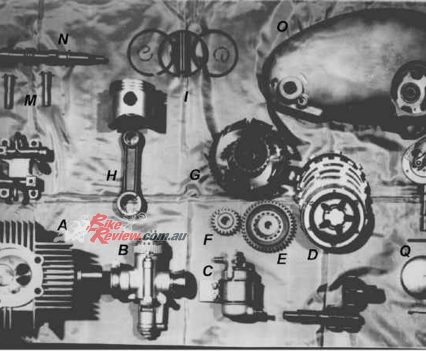

The Catria family formed the backbone of MotoBi’s future four-stroke range, progressively upsized from the 62 x 57mm 175cc base version, first in 1963 to an overbored 66.5 x 57mm 200cc model called the Sprite, then in 1966 to a full 74mm-bore 250cc version whose Sport Special performance kit delivered a heady 150km/h in street guise. This OHV single stayed in production until 1973, by which time it had been badged as a Benelli to form part of the Pesaro firm’s 1960s annual production peaking at 90,000 units, which had led to Alessandro de Tomaso acquiring it in 1972.

For peace had broken out after Giuseppe Benelli’s passing, and in November 1961 MotoBi was absorbed into the family empire, to form the Gruppo Benelli-MotoBi. For the rest of the decade MotoBi motorcycles were in fact marketed as the more sporting lightweight products of the Benelli company, aimed at providing customers with a bike they could ride to work one day, then compete with in their local hill-climb or road race the next.

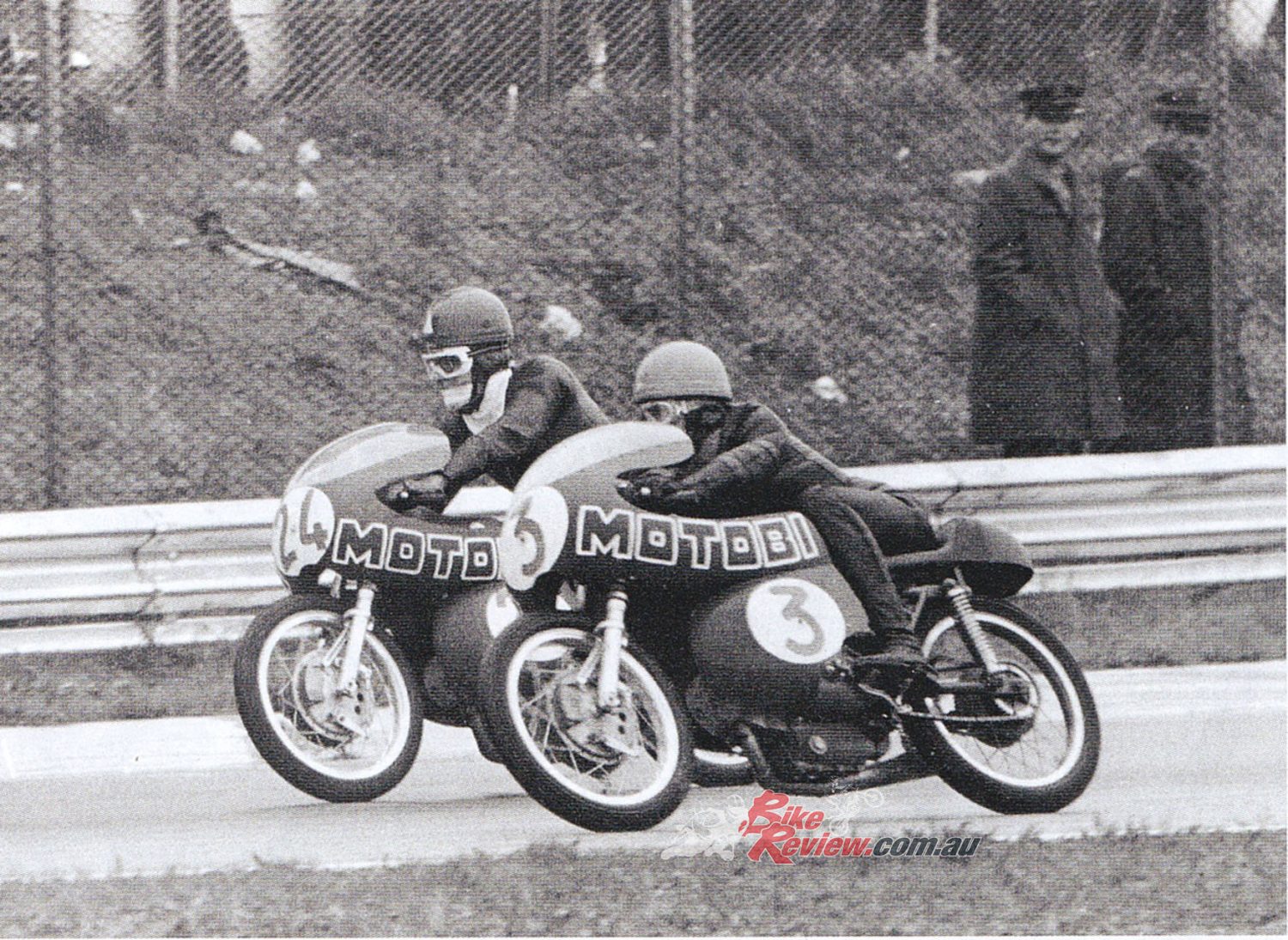

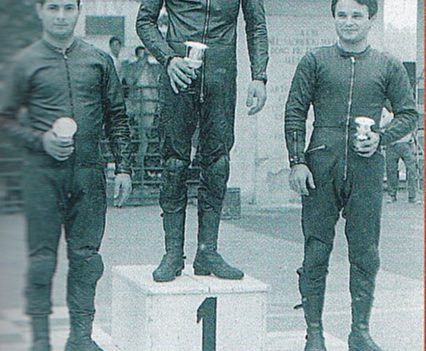

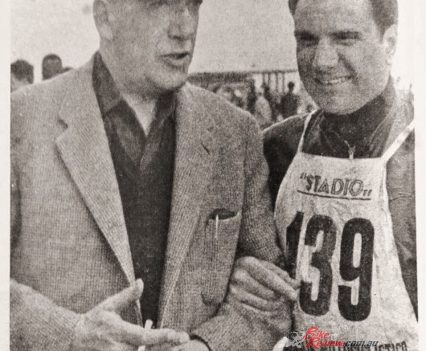

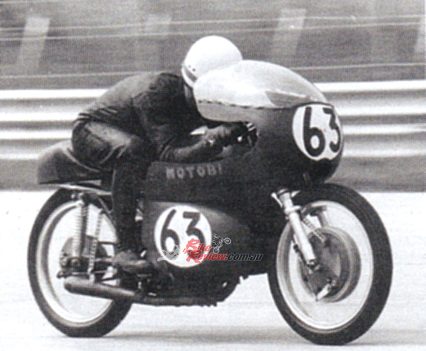

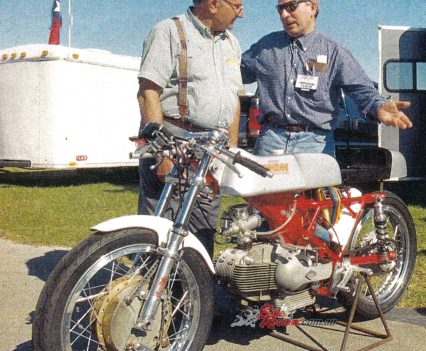

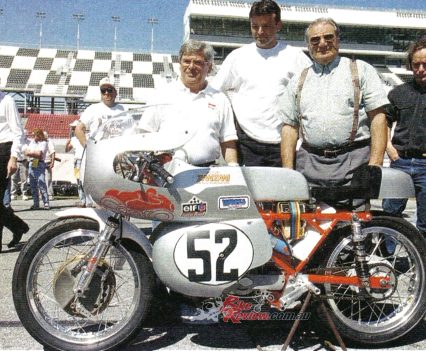

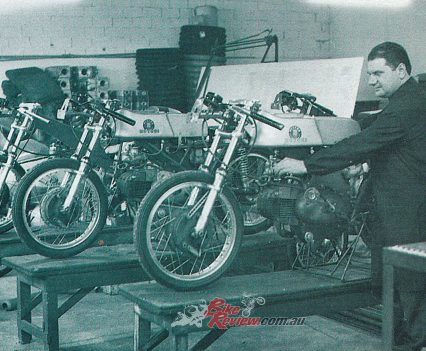

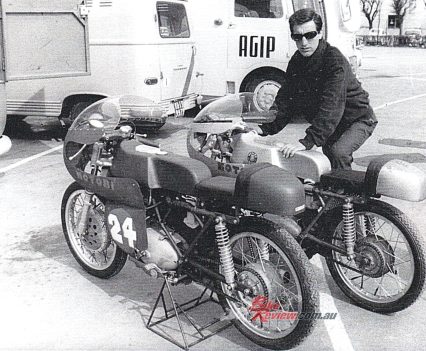

1962 Primo Zanzani-C in MotoBi Reparto Corse with Marco Benelli on his right! After Benelli joined with MotoBi.

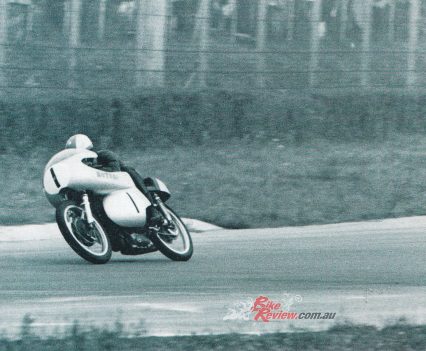

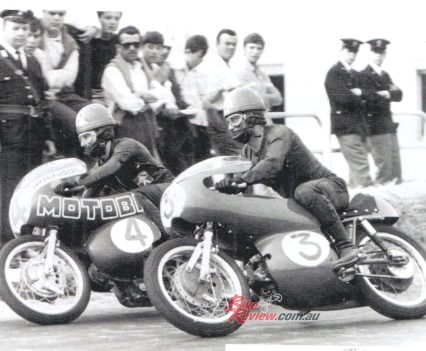

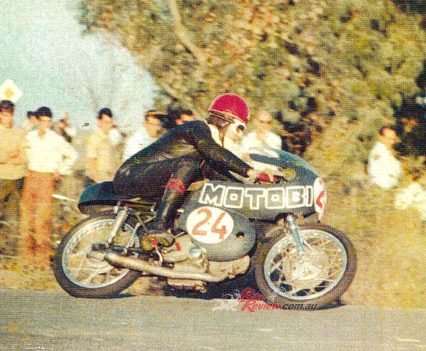

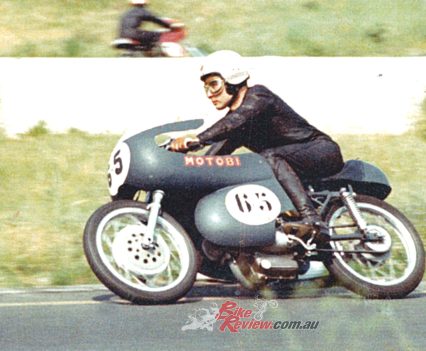

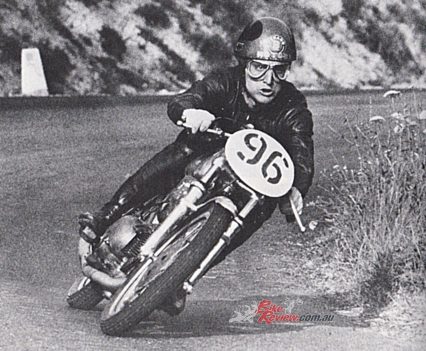

The MotoBi Catria was a true production racer, tailor-made for success in Italy’s thriving MSDS (Moto Sportive Derivate dalla Serie, aka Formula 3 Junior) Modified Production category, one step down from National-level racing with purebred racers. It was competitive in both the 125cc and 175cc classes this originally catered for, as well as in the 250cc category that came later. MotoBi-mounted riders won 16 MSDS Italian Junior championships all told in the 1960s, providing the stepping stone to a Grand Prix career for famous names like Roberto Gallina and future World champions Eugenio Lazzarini, Paolo Pileri and Pierpaolo Bianchi. MotoBi was a brand largely unknown outside Italy, except in the USA, where its models were imported by Cosmopolitan Motors as part of their Benelli distribution deal – even if many were rebadged as Benellis, or else sold through the giant Montgomery Ward department store chain as Ward Riversides.

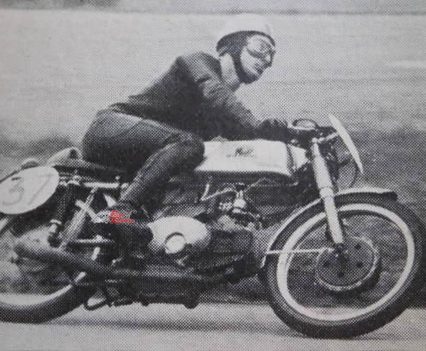

The Wise family which owned Cosmo realised there was room to establish the MotoBi name through competition, bringing in a handful of factory-developed Formula 3 racers aboard which established names like Kurt Liebmann and Jess Thomas competed successfully in the USA and Canada. It was Texan Thomas who delivered the most illustrious sporting moment in MotoBi’s history, when on his pushrod Italian single he defeated a pair of works Honda RC162 fours on the Daytona infield circuit to win the 1962 U.S. GP.

Check out our other Throwback Thursdays here…

He campaigned his tuned 175 MotoBi bored out to 207cc via sandcast crankcases, a roller-bearing bottom end and needle-roller gearbox, to 26 race wins that season. One of the men Benelli sent to America later that decade to help Cosmo put MotoBi on the map was a Pesaro factory race mechanic named Eraldo Ferracci, who ended up staying on in the USA and carving out a flourishing reputation for himself as a tuner. He eventually won the 1991 World Superbike Championship with Doug Polen riding his privateer FBF/Fast By Ferracci Ducati 888!

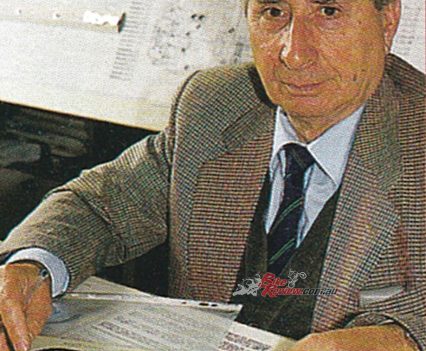

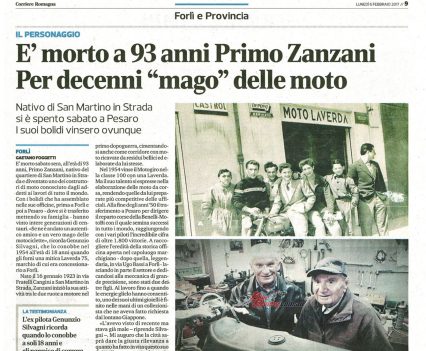

The man whom Ferracci had worked under in Italy was Primo Zanzani, a former racer from Forlí who’d been enlisted by Luigi and Marco Benelli to take over the MotoBi race shop in 1957 on the death of their father. A self-taught tuner and former winner of the gruelling Motogiro’s 100cc class on a Laverda, winning four of the six stages, Zanzani was the man tasked with turning the four-stroke MotoBi models into such competitive hardware in both Italy and the USA in the early ‘60s.

Zanzani was the man tasked with turning the four-stroke MotoBi models into such competitive hardware in both Italy and the USA in the early ‘60s. He moved to MotoBi full time in 1966, to work again on modifying production models.

This feat duly earned him the role of developing the four-cylinder Benelli 250GP racer from 1962 onwards, when the two companies were united. Having helped turn it into a Grand Prix race-winner in the hands of Tarquinio Provini, but in the process fallen out with chief engineer Giovanni Benelli over what he believed (correctly, as it turned out) was a fundamental error in the design of the four-cylinder Benelli 250GP motor, Zanzani moved back to MotoBi full time in 1966, to work again on modifying production models.

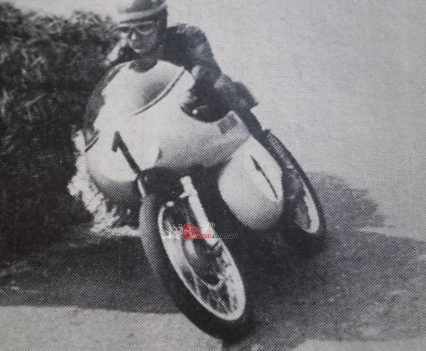

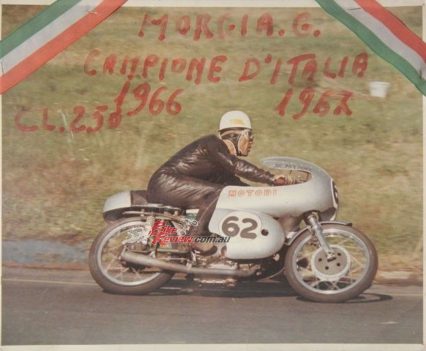

There, Zanzani focused his attention on the new 250cc Sprite model introduced that year, with the specific purpose of making it a winner in the recently-introduced quarter-litre MSDS class for customers of the Pesaro factory. The fact that MotoBi won the Italian 250cc Junior title in 1966, ’67 and ’69 shows how well Zanzani succeeded in the face of intense competition from rival factories like Ducati, Aermacchi, Parilla and Morini – though perhaps the most glorious display of the bike’s performance came at Daytona in 1967, in the 250cc support race for the Daytona 200.

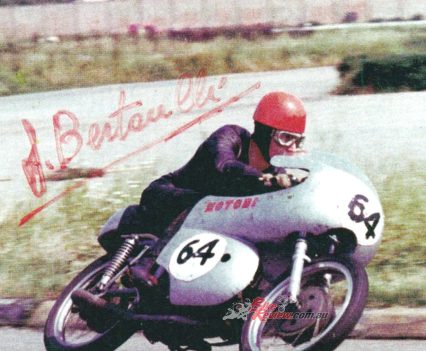

In that, an unknown rider named Sam Bertarell aboard an OHV MotoBi four-stroke single spent the entire race run on the full 3.81mile banked circuit battling with Florida’s Kenny Stephens on one of the very fast then-new TD2 Yamaha two-stroke twins, before gapping him in the infield on the final lap to win the race. It turned out that Sam was really future 500GP podium finisher Silvano Bertarelli, riding under an alias since the Italian Federation wouldn’t grant any of its riders permission to race at Daytona! This highly impressive result certainly helped Cosmo’s Motobi sales drive in the USA.

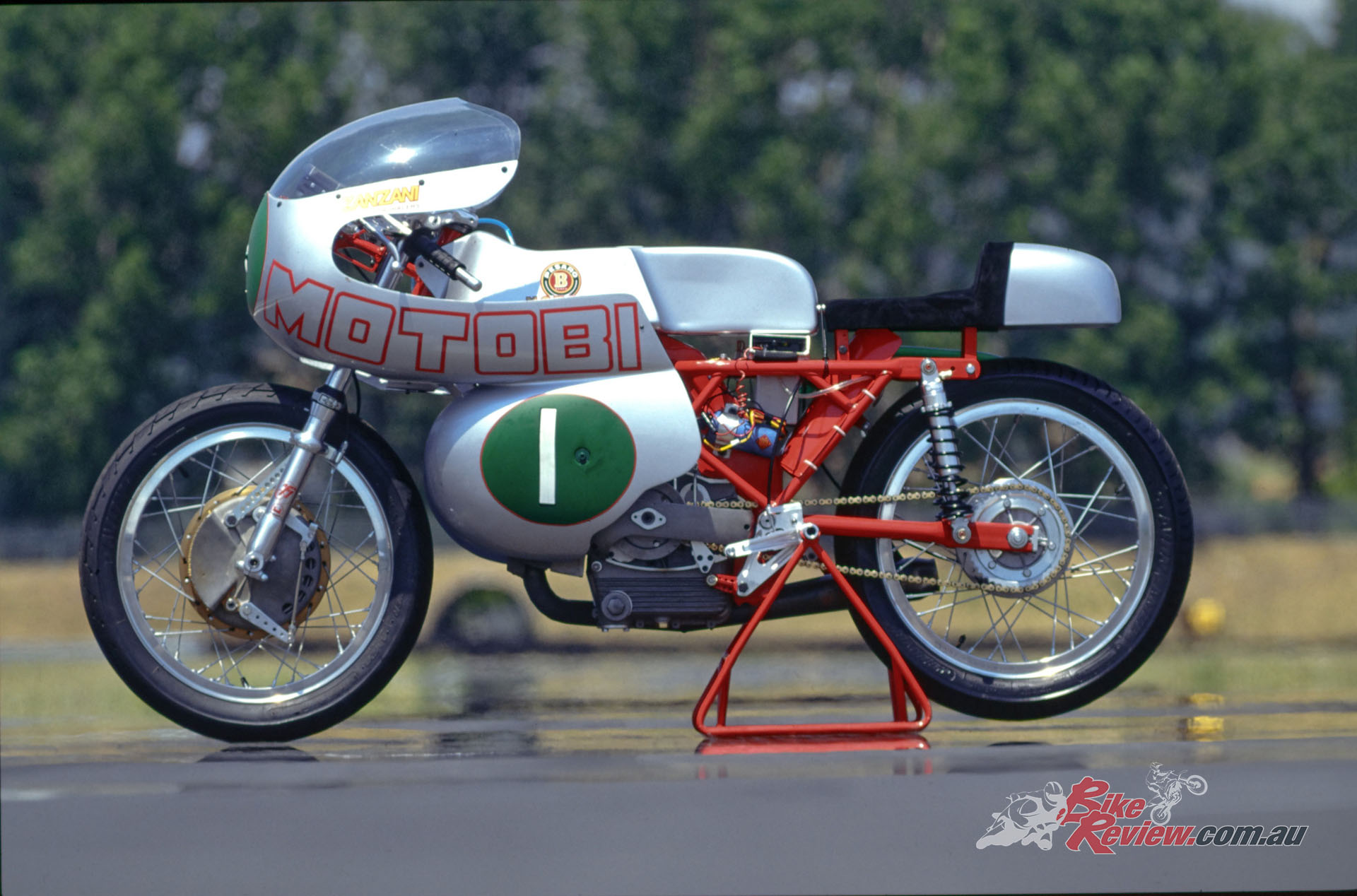

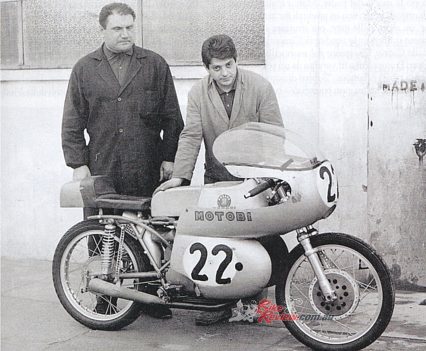

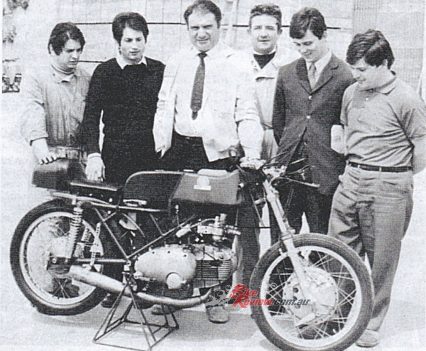

To make MotoBi such a competitive contender for top honours, Zanzani created just nine examples between 1965 and 1973 of a limited edition homologation special known as the 250cc MotoBi Sei Tiranti (six-stud).

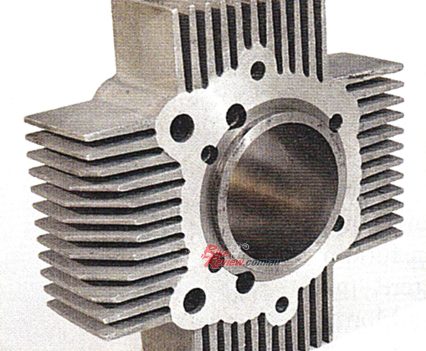

To make MotoBi such a competitive contender for top honours, Zanzani created just nine examples between 1965 and 1973 of a limited edition homologation special known as the 250cc MotoBi Sei Tiranti (six-stud). This had six cylinder head studs instead of the street Sprite’s four, to resolve problems with cylinder head sealing when compression and engine speeds were raised in pursuit of power – and considering that by the end of the decade Zanzani had more than doubled the 16hp output of the street 250 Sprite to 36hp in MSDS form, this was hardly surprising!

So an extra pair of studs was grafted in to bolt the cylinder head on tight to what on this tricked-out special were sandcast crankcases for extra stiffness, rather than the diecast ones of the streetbike – for this was a silhouette class, where every little trick was employed to gain an added edge.

Cathcart rode both the customer bike and the factory machine! Make sure you check out his racer test.

Sadly, the global Japanese onslaught meant diminishing sales and no budget for racing, so in 1970 the MotoBi factory race department was closed, leaving Zanzani to start his own machine shop operation in Pesaro, where he built another 15 Sei Tiranti racers in the early ’70s. But in parallel with this, Zanzani developed a specialist expertise in the disc brake technology then new to motorcycles, but which he’d been the first in the world to adopt on any GP racer back in 1965 on the four-cylinder Benelli 250, using US-made Airheart discs rather than the Campagnolo disc brakes then produced in Italy for lightweight 50/125GP machines.

Developing his own process for plasma-spraying aluminium disc rotors with iron to produce a far lighter disc brake assembly than the steel or cast iron discs then commercially available (with the additional benefits of reducing both unsprung weight, and their gyroscopic effect on handling), Zanzani’s brakes became ubiquitous components on GP racers in the smaller classes, winning no less than 24 World Championships in the 50/80/125/250GP classes from 1978 on, up to and including Alessandro Gramigni’s 125GP Aprilia World crown in 1992.

Thereafter, together with his two sons Athos and Mirko, Primo Zanzani continued to run the trio of high-tech machine shops he owned in Pesaro, producing intricate components for the local woodworking machinery industry – and complete MotoBi 250 Sei Tiranti replicas! He passed away in November 2017, aged 93, after a long and productive, but also highly passionate life on two wheels.

MotoBi Historical Gallery

Editor’s Note: If you are reading this article on any website other than BikeReview.com.au, please report it to BikeReview via our contact page, as it has been stolen or re-published without authority.