The Vincent-HRD Series A Rapide. A page-turner in the evolution of the motorcycle, with its engine designed by Phil Irving, it is the world’s first Superbike, faster and rarer in street form than the Brough Superior SS100. Photos: Bonhams/Kel Edge.

Even now when you can buy a racer-with-lights like a BMW M 1000 RR, Ducati V4R or Bimota KB 998, and ride it on the public highway in OZ, street registered, the achievements of London lad Jim Kentish with the Rapide Series A in the summer of 1938 do merit attention…

Performance came at a price, with the Series A Rapide costing £138 new, including a speedo and eight-day clock…

Evidently not short of a bob [buck] or two, on 10th March 1938 the 20-year old Kentish had become the 21st out of the 78 customers of the Stevenage-based Vincent-HRD Motorcycle Co. owned by Phillip Vincent, to purchase what back then was the fastest thing on two wheels anywhere in the world that was both street legal, and available to order. That was the company’s Series A Rapide, which had made its public debut at the London Olympia Show on 2nd November 1936.

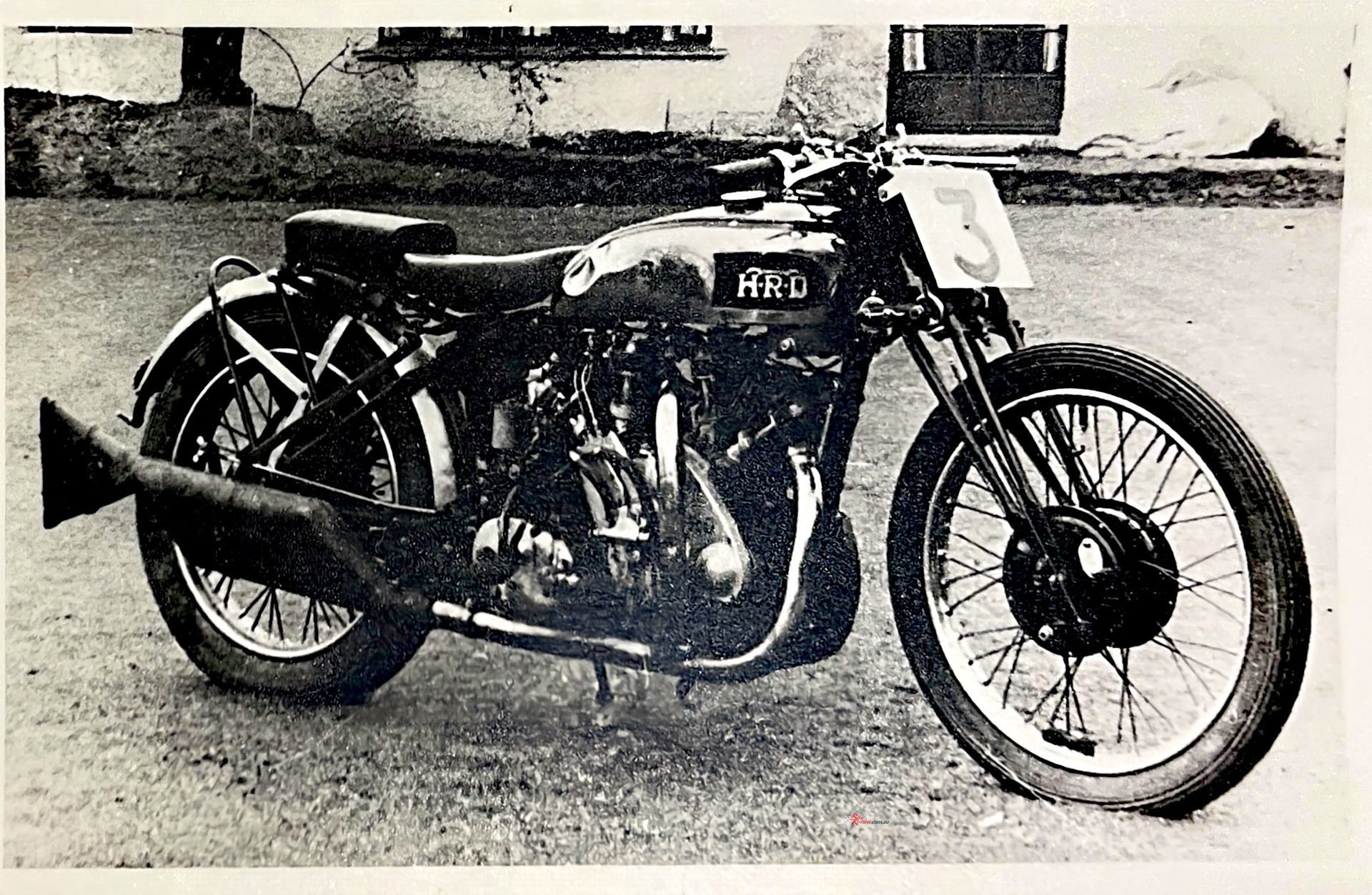

Designed by the legendary Australian engineer Phil Irving, this 998cc high-camshaft OHV 47.5° V-twin producing 45 bhp at 5,500rpm was independently timed at 110mph in as-delivered customer guise…

Designed by the legendary Australian engineer Phil Irving, this 998cc high-camshaft OHV 47.5° V-twin producing 45 bhp at 5,500rpm was independently timed at 110mph in as-delivered customer guise. It thus emphatically surpassed its greatest contemporary rival, the JAP/Matchless-engined Brough Superior SS100, which as per its name was ‘only’ good for 100mph!

But this performance came at a price, with the Series A Rapide costing £138 new, including a speedo and eight-day clock. Perhaps this was what deterred more customers from signing a VMC order form in that first year in production, given that the company had never previously built anything larger than a 500cc single. But Jim Kentish wasn’t deterred by that – and there’s hard evidence to prove that his purchase completely lived up to his expectations.

For having obtained his motorbike licence at the age of 16, Kentish was a dedicated biker for the rest of his long life. When he passed away in 2006 at the grand age of 90, he hadn’t owned a car for the previous 30 years, and after building up a large yachting accessory business on England’s South Coast, he’d sold it and turned to two-wheeled touring in a big way, criss-crossing the British Isles and Continental Europe on a succession of BMWs. Aged 80, and unmarried, he decided to move into a retirement home, and swapped the four-cylinder K100 ‘flying brick’ BMW he was then riding for a new, lighter R 1100 Boxer twin as his ‘knees were getting weak’, and he wanted something less daunting for his declining years. “This I really enjoyed, and it caused quite a sensation among the old folks at the home!” he wrote to a friend. I bet! He kept riding the Beemer right up until the day he died.

But back to the future, and in late August 1938 after five months’ ownership of the Vincent-HRD Rapide, Jim Kentish decided to ride down to the Brooklands Motor Circuit, just a dozen miles from his Richmond, Surrey home, for a midweek practice day in which he presumably hoped to find out ‘what’ll she do’. But after a couple of runs he was stopped by the Dunlop Tyres rep, to be told that he’d been lapping at ‘over a hundred’ [mph], but should not have been going that fast using road tyres. Hmm – time to get serious…

There was a race meeting at Brooklands the following Saturday, 3rd September, with a three-lap handicap on the banked Outer Circuit for which Kentish and the Rapide were eligible. But Jim was then working behind the scenes at the Richmond Theatre as the Stage Manager, responsible for arranging the sets for each play performed there, so going racing would involve some finagling because that day there were two performances, an afternoon Matinee and an Evening show.

Forgoing any Friday night socialising in favour of preparing the stage for the next day’s afternoon show, Jim Kentish rode the Rapide down to Brooklands next morning, and readied himself for his first ever race – including fitting the Vincent with 20-inch Dunlop racing tyres! Perhaps fortuitously in view of his theatre commitments, his was the first race of the day, for which he’d been placed on the Scratch mark by the handicapper owing to the Vincent’s presumed speed, meaning he’d have to overtake every one of the two dozen other starters in order to win the race.

“He’d averaged over 100mph for the entire three-lap event, with a fastest lap of 106.65mph which earned him the Gold Star – on his road bike!”

Well, the results show Jim Kentish did exactly that, coming from behind to overhaul Brooklands regular Basil Keys’ Norton single on the run to the flag. At a time when earning a coveted Brooklands Gold Star by lapping at over 100mph in a race was the height of ambition for most Motor Circuit competitors, the inexperienced 21-year old had won one in his very first race! Indeed, he’d averaged over 100mph for the entire three-lap event, with a fastest lap of 106.65mph which earned him the Gold Star – on his road bike! Indeed, after perfunctory but no doubt heartfelt celebration amid congratulations from all and sundry, Jim Kentish then packed up his gear, tied it to the back of the Vincent, and rode back to Richmond Theatre in time to set the stage for the evening performance. A good day’s work!

Jim’s recollections of that debut race were later enshrined in print in MPH, the Vincent Owners Club’s magazine. “We lined up for the race, and I felt horribly out of place with fearsome track machines on either side, drilled almost transparent with holes, and with handlebars which made me want to laugh. There were plenty of glances at my machine, complete with mudguards, dynamo, tool box, etc. But then we were off! What fun that ride was, and how soon it was all over! On returning to the Paddock I was told I had won my Gold Star at 106mph.” He later donated the award to the Brooklands Museum, where it sits on display today. His victory was enshrined in print in the following Wednesday’s copy of the ’Green ‘Un’ – the weekly Motor Cycling magazine – which published a photo of Jim on the Rapide clearly motoring very hard to overhaul Basil Keys’ Norton on the run to the finishing line.

Read Sir Al’s previous Throwback Thursday articles here…

In the course of Brooklands’ 33 years of operation, only 25 Gold Stars were awarded in the 1,000cc category known as Class E, compared with exactly 100 in the 500cc class. During the time that the Series A Rapide was in production (1937-1939) there were only seven awarded for such bikes in the 1,000cc class, including that of Jim Kentish. Vincent-HRD works riders Ginger Wood and George Brown are both believed to have lapped Brooklands at over 100mph on Series A Rapides, but neither features in the accepted list of Class E Gold Star recipients. Whatever the case, Jim was in exalted company.

Only one thing wrong: he’d been bitten by the racing bug, and despite achieving his ambition first time of asking, Jim Kentish had had so much fun doing so that he wanted more of the same – even if his Vincent-HRD road bike might need a little extra oomph to compete against the larger-capacity Brooklands racebikes. Let’s hear from Jim what happened next, per his article in MPH. “A phone call to P. C. Vincent explaining my troubles – and the fact that I had been talked into entering for the five-lap Outer Circuit handicap race on the following weekend – produced the sort of service for which the firm has always been noted. The bike was collected, rebuilt (and between you and me, secretly breathed on, I think) and returned in three days.”

With Dunlop racing tyres still fitted, Jim Kentish returned to the track the following Saturday, 10th September, lining up aboard the Vincent in the MCC/Motor Cycling Club’s unique annual race meeting for both cars and bikes. He was in fact entered in three races, the first being a two-lap Handicap on the Outer Circuit which he won at an average speed of 100.61mph, with once again a best flying lap of 106mph. Two wins from his first two starts – this racing game is fun, isn’t it?! Unfortunately, the other side of the coin then manifested itself in the next event, a One-Hour High-Speed Trial in which riders attempted to cover a fixed number of laps to gain a First Class Award.

Motor Cycling’s reporter noted there were 17 different makes represented among the 50-odd starters, and that after moving to the Home Banking to watch so-called riding methods, observed that “particularly good were those of J.F. Kentish (998 Vincent-HRD), until he disappeared from the scene with a piston failure.” Oops! Had the Vincent Works perhaps breathed too hard on the Series A motor? We’ll never know – but let’s hope Jim had arranged for someone else to set the stage for that evening’s Richmond Theatre show!

The Vincent factory presumably rebuilt the motor in time for Kentish to contest three more races at the October 8 Brooklands meeting, and a pair of races each in further events held in March, April and June 1939 – but sadly, the results of those races have gone missing. In between, he also competed with the Rapide in the 1938 ACU Rally and the ‘39 MCC Land’s End Trial, each with some gruelling offroad sections [see photo] which must have represented the equivalent of riding a Ducati V4R Superbike in the ISDE!

But the clouds of war were becoming ever darker, and after a solitary ride at the June 24 Brooklands meeting, Jim Kentish called a temporary halt to his racing career. Selling the Rapide on the outbreak of WW2 that September, he joined the Territorial Army Military Police as a motorcyclist, serving under Sir Malcolm Campbell, the former World Land Speed Record holder in his Bluebell car, before being transferred to the Royal Signals as a despatch rider, and eventually becoming a commissioned officer. Clearly a formidable, multi-talented rider, Jim Kentish resumed his competition career post-WW2, competing in the ISDT (as it was then) on three occasions: in 1949 on a 350 BSA, in 1950 on a works prototype 500cc Matchless twin, and in 1954 on a 225cc James Colonel two-stroke single, winning a Silver Medal on that.

Jim Kentish also road raced in the Isle of Man’s Manx Grand Prix in 1947 on a 350 Norton tuned by his neighbour Francis Beart, finishing the Junior TT before winning a Replica in the Senior race by finishing 17th on his undersize 350 – quite a feat. He then transferred to the Junior TT in 1949 on one of the then-new AJS 7Rs. Sadly, Kentish dropped the bike in practice and it caught fire, but AMC Sales Manager Jock West stepped in and had it restored at the Plumstead factory, allowing Jim Kentish win the Ulster GP Handicap race on the bike three months later. In 1950 and 1951 he finished the Junior TT on the 7R, winning a Replica in the latter year. Jim Kentish then became the Southern Area sales manager for Royal Enfield, but became impatient with the tired and out-of-touch management in the motorcycle industry at large, so by now living in Southampton, he left to set up his own yachting accessories business on the Solent.

Check out our other Vincent motorcycle content here…

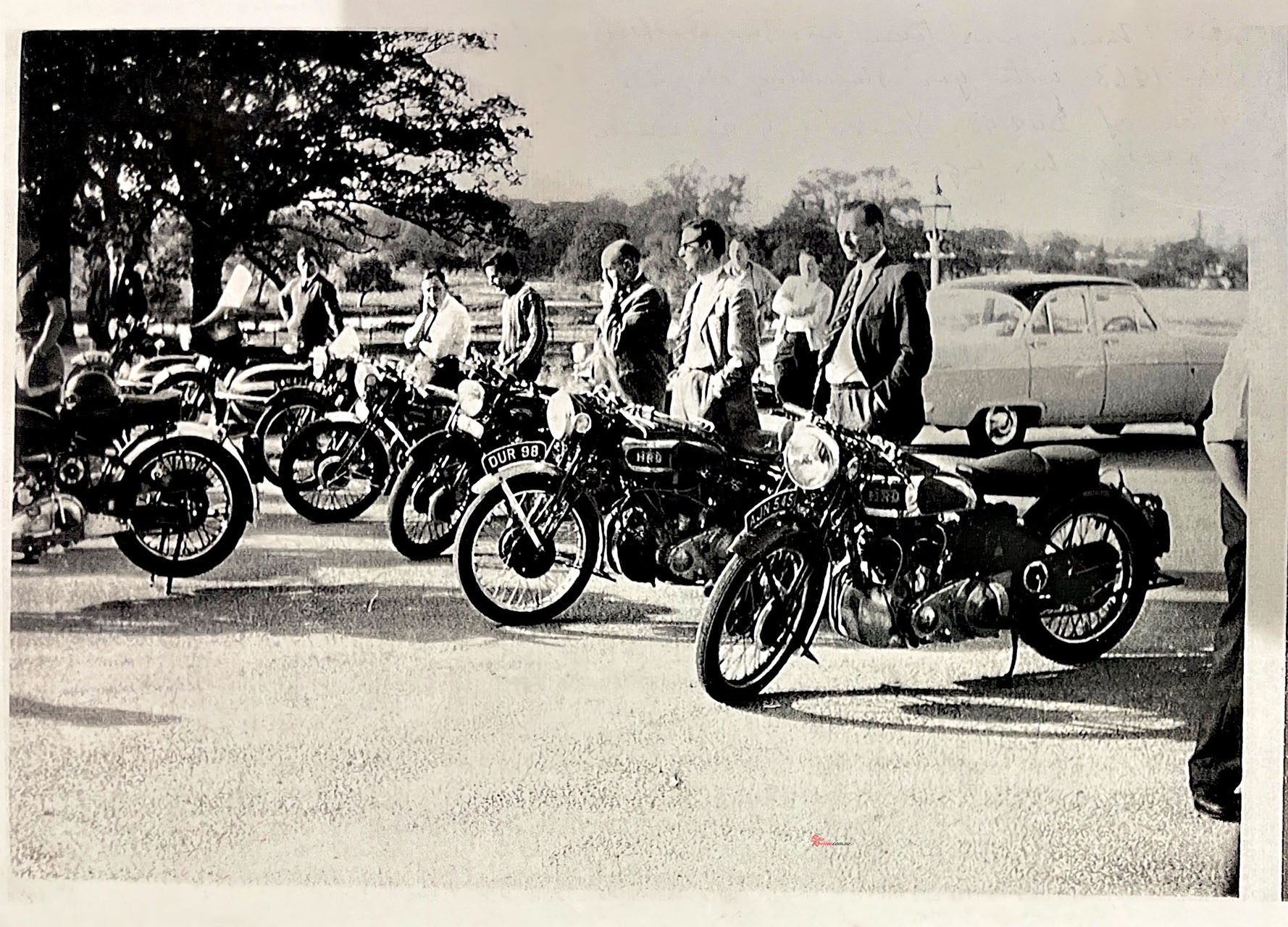

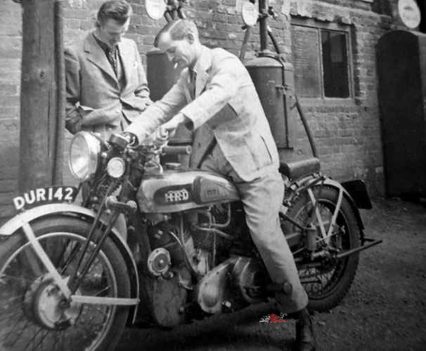

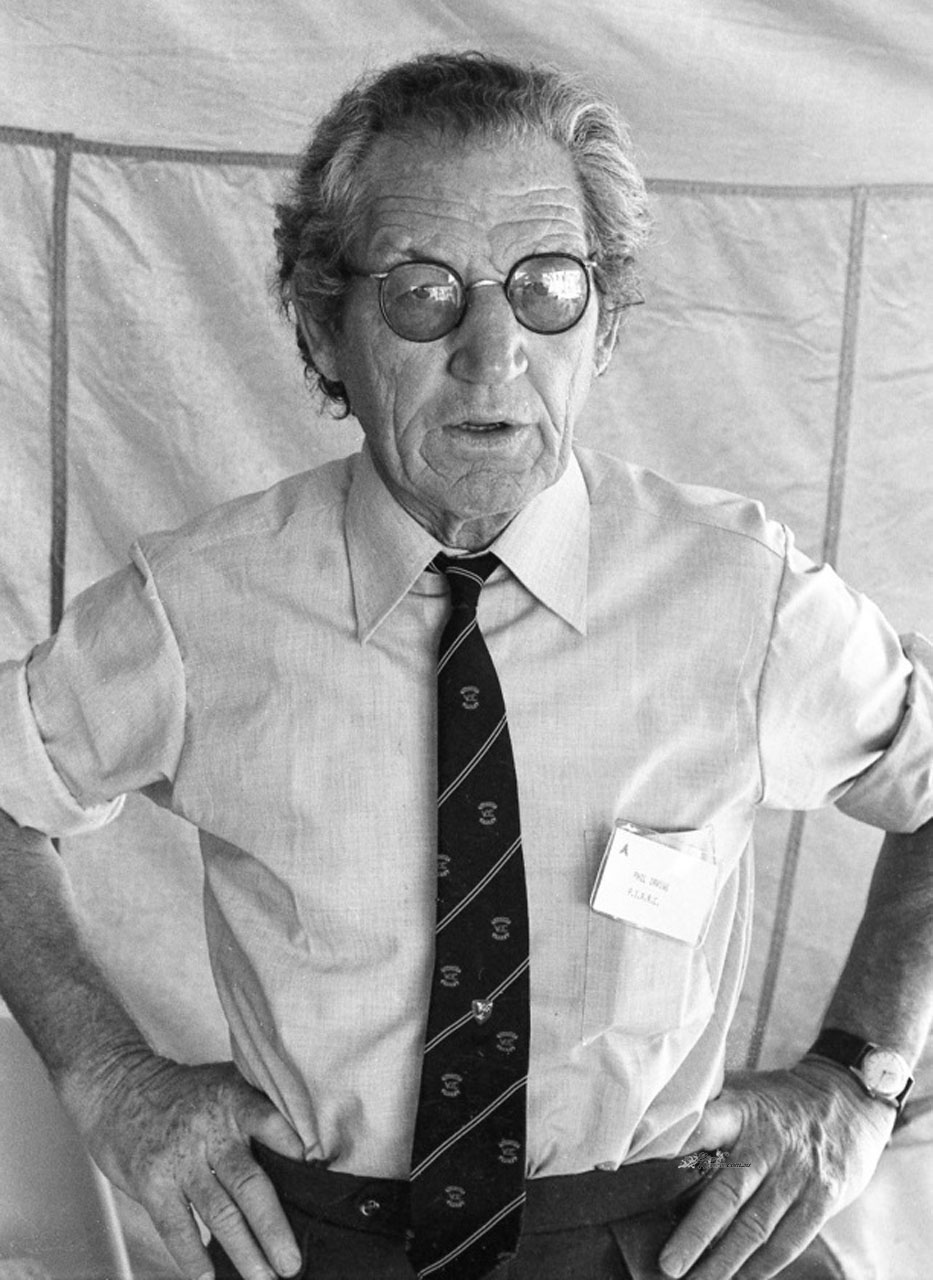

The Kentish Vincent Rapide bearing reg.no. DUR 98 went through a couple of other owners before fetching up in the hands of one Harry Ainsworth Parkinson of Staines, Middlesex on 21st April 1953. Still very much complete and in running order, it was then purchased by a near neighbour of his on 20th October 1961 whom auction protocols forbid me naming. That’s because that owner has consigned the bike to the Bonhams sale at the UK’s Stafford Classic Show on April 26-27. In 1963 he’d brought the bike to the Vincent OC’s Series A Rally at The Belfry, NE of Birmingham, where Jim Kentish was reunited with it [see photo]. In 1986, still a runner but increasingly well-worn, he had the complete bike restored by marque specialist Tony Wilson, after which the Series A Rapide was kept inside his house as a static exhibit, and not ridden again since the rebuild’s completion.

A nicely mellowed older restoration, DUR 98 thus represents a rare opportunity to own and enjoy one of only a tiny handful of Series A Rapides with Brooklands racing history. Price? Well, with only 78 examples built, and around 50 known survivors, such bikes come up very rarely, making it quite a coincidence that Bonhams sold an identical motorcycle at the same sale last year for £228,850 ($463,548.49 AUD) incl. premium. This was in fact bike no.17, just four earlier than the Kentish machine, but had been reassembled from a box of bits for a Japanese owner, and had no racing history unlike Jim’s bike, which has matching Upper and Rear frame nos. DV1522 and Engine no. V1021. It’ll be interesting to see what it makes!

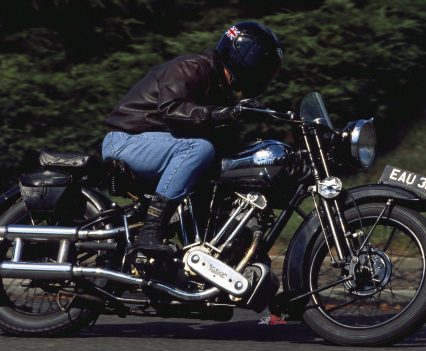

One can only speculate if the new owner ends up riding it, but in that case I am fortunate to be able to give him or her a taste of what’s in store. That’s because thanks to the ever-generous Sammy Miller I once spent a sunny spring afternoon riding the Series A Rapide that’s been on display in his eponymous Museum on England’s South Coast www.sammymiller.co.uk since 2005. This is a later machine, no.59, ordered on 13th February 1939, which came to Sammy from a UK collector complete save for the rear cylinder-head. He and his then assistant, the now retired Bob Stanley, restored it to original running order, and I was able to ride it in something approaching anger along the mile-plus private driveway of one of Sammy’s near-neighbours.

“The Vincent’s performance is as muscular as it looks, torquey and insistent as the speedo needle sweeps round the dial”…

I’ve been fortunate to ride many different Vincent V-twins down the years, and even to race a couple. That includes a genuine Black Lightning which was the ne plus ultra full-race version that became a benchmark for record-breaking, both in a straight line and going round and round a circuit. To finally ride the progenitor of all these motorcycles was both personally satisfying, and very illuminating. For the two Phils got it right first time, and as the former owner of a Brough Superior SS100 built one year before the Jim Kentish bike, on which I covered around 800 miles in the two years I owned it in those pre-telephone number price days, I can only imagine George Brough’s reaction when he rode a Series A Vincent-HRD – as he surely would have done.

Despair, coupled with barely suppressed admiration, would have been George’s response to the Rapide’s amazing performance, for this is worthy of a motorcycle built 30 or even more years later, and puts the comparable Brough in the shade. I’ll admit that even with the nowadays lowly 6.8:1 compression ratio, kickstarting it into action via the right-side lever proved beyond my talents, even using the fat decompressor lever on the left ‘bar. So in the end Bob Stanley did it for me first time of asking, and for the rest of the time I resorted to a run-and-bump technique well-honed in decades of Classic racing. But the V-twin engine certainly lets you know when it’s fired up and ready for action, as this is both a loud and noisy motorcycle – not necessarily the same thing. Noisy, because with all the exposed valvegear and the tight engine clearances aimed at high performance, there’s quite a mechanical clatter to the Vincent motor – and you also won’t want to wear light-coloured pants/trousers riding this bike, either, because there’s quite a bit of extraneous lubricant chucked about.

The two-into-one straight-pipe exhaust with its nominal silencer about eight inches from its end is however loud, angry and just bellows performance when you fire it up…

The two-into-one straight-pipe exhaust with its nominal silencer about eight inches from its end is however loud, angry and just bellows performance when you fire it up – if ever a bike sounded ready for action it’s this one, and by comparison the twin fishtail-exits of ‘my’ Brough’s exhaust were much more subdued. The Vincent seems like a racer-with-lights, the Brough more of a gentleman’s express. Lift the right-foot lever for bottom gear, noting as you do so that the clutch action is quite light yet positive, and the gearshift firm, yet precise, with no undue graunches selecting a gear at rest. There’s no tacho fitted – the ‘other’ instrument besides the 120mph Smiths speedo on the right is a Roman-numeral eight-day clock – but I didn’t have to slip the clutch very much in departing the scene, for the Vincent Rapide is just raring for action.

“The riding position felt quite close-coupled, but not cramped, with the relatively short, flat handlebar reminiscent of so many BMW’s”…

First gear on the four-speed Burman ‘box is quite long, so I changed into second gear at 25mph, with no real sense of going through neutral to do so, and now the Rapide was living up to its name. The Vincent’s performance is as muscular as it looks, torquey and insistent as the speedo needle sweeps round the dial. 40mph seemed the right speed to select third gear, and still the engine kept on pulling hard before short-shifting into top gear at 65mph. Sadly I didn’t have the room to explore ultimate top speed performance on this freshly rebuilt bike with just eleven miles on the clock when I started riding it, after Sammy had instructed me to ‘see what’ll she do’!

But honestly, the level of performance once what at 430lb/195kg dry is quite a heavy bike had got up and running, was genuinely impressive, with outstanding top gear roll-on. It was also surprisingly smooth for a 47.5° V-twin with no balance shaft, only tingling if I held on to second gear too long. I can think of quite a few 1960s-‘70s one-litre or thereabouts V-twins which the ‘30s Rapide would have given the hurry-up to – and this is a streetbike, remember, not the tuned Ginger Wood works racer which supposedly did 130mph at Donington Park. For 1937 it must have been a bike from another planet for even a skilled and experienced high-speed rider, compared to what he’d have ridden before.

Tubular-steel, open loop, engine stressed member, friction damped Brampton girder forks, cantilever swingar with two Vincent hydraulic shocks.

The riding position felt quite close-coupled, but not cramped, with the relatively short, flat handlebar reminiscent of so many BMW’s encouraging you to lean forward at speed, tucking your elbows in over your knees to present a suitably wind-cheating stance. It feels very natural and untiring, and the Dunlop Drilastic saddle has enough give in the springs to supplement the Vincent’s unique (for back then) cantilever rear suspension.

You feel this most when you push back beyond the saddle to park your derriere on the unsprung bumpad carried on a subframe above the rear mudguard, for although there are precious few bumps on the driveway I was riding on, you could feel the suspension working when descending in to a deep dip in the road and up the other side. The future began here, and the Vincent Rapide was the signpost.

That was especially true of the Rapide’s brakes, for unlike my Brough Superior’s quite inadequate solitary seven-inch [178mm] Enfield single leading-shoe front drum, on the Vincent Rapide there are two – and at each end of the bike, too. OK, all four of these aren’t the same as a set of discs in hauling down such a heavy bike as the Rapide from ton-up speeds – but in the context of their era these were quite exceptional, and kept on working even after repeated stops from high speed at my test route’s front gate. Job done.

The Vincent-HRD Series A Rapide was truly a page-turner in the evolution of the motorcycle. Not only does it have real visual presence thanks to its undeniably handsome, broad-shouldered appearance, with its high-set camshafts and relatively short cylinders endowing this magnificent motorcycle with a look for the ages, it also established an enviable reputation around the world as the leading-edge technical benchmark of motorcycling excellence, both in engine performance and frame design. It was indeed the bike of the future at least 25 years before its time. I reckon whoever purchases the ex-Jim Kentish bike will not only have deep pockets, but good taste as well.

1936 Vincent-HRD Series A Rapide Specifications

ENGINE: Air-cooled dry sump high-camshaft OHV 47.5-degree V-twin four-stroke with two valves per cylinder, 84 x 90mm bore x stroke, 998cc, 6.8:1 compression, 2 x 1 1/16th (27mm) Amal Type 29 carburettors with remote float chambers, Miller Magdyno ignition, Burman four-speed gearbox with duplex chain primary drive, multi-plate oil-bath clutch, two-into-one straight-pipe exhaust.

CHASSIS: Tubular-steel, open loop, engine stressed member, friction damped Brampton girder forks, cantilever swingar with two Vincent hydraulic shocks, 2 x 7in/178mm Vincent leading shoe drum brakes front and rear, Front: 3.00 x 20 Avon Racing on WM1/1.60 in. wire-laced Dunlop aluminium-rim wheel (Miller bike idem), Rear: 3.50 x 19 Avon GP on WM2/1.85 in. wire-laced Dunlop aluminium-rim wheel (Miller bike: 3.25 x 19 Dunlop Gold Seal K70), 1473mm wheelbase, 787mm seat height, 16L fuel capacity.

PERFORMANCE: 195kg dry, 45hp@5,500rpm, 177km/h top speed.

OWNER: On consignment for Bonham’s sale April 27 2025 auction…