50 years ago today on June 28, 1975, Barry Sheene won his first 500 GP, Suzuki's first for the RG, only a few months after his near career and life ending horrific Daytona crash. Sir Al tells the story, and rides the bike... Photos: Kyoichi Nakamura

Fifty years ago the Suzuki RG500 made its competition debut, and in doing so raised the curtain on the modern era of 500cc Grand Prix racing, by making factory-level Japanese four-cylinder performance available to privateers for the first time. In June 1975, it won…

Before the first 25-bike batch of Mark 1 RG500s went on sale late in 1975 for the 1976 season, the paddocks of the Continental Circus had been packed with a stopgap selection of arcane bikes, whether four-stroke multis like the Italian twins and factory fours, diehard British singles, or the prototypes of the soon-to-be-supreme Japanese two-strokes, headed by nominally overbored 350 Yamahas and the first-generation air-cooled customer 500s, like the TR500 Suzuki twins and Kawasaki H1R triples. Against this transitional Heinz 57 cocktail, works four-cylinder hardware like the MV Agusta and YZR500 Yamaha had an easy time of it.

Before the first 25-bike batch of Mark 1 RG500s went on sale late in 1975 for the 1976 season, the paddocks of the Continental Circus had been packed with a stopgap selection of arcane bikes.

But the RG500 changed all that. Though it’s become something of a cliché to stamp the Suzuki as the Manx Norton of the two-stroke Grand Prix era, that’s exactly what it was. For a full decade from 1976-86, the rotary-valve square-four packed GP grids around the world, whether in the form of full-on factory entries, most often run by British importer Heron Suzuki, or as the racer of choice for the dedicated privateer. To underline the immediate success enjoyed by the eager customers awaiting the bike’s debut, just take a look at the 1976 World Championship, the first year the production RG500 was available for purchase, when 58 bikes ended up being delivered to customers.

For a full decade from 1976-86, the rotary-valve square-four packed GP grids around the world…

No less that the first 12 riders in the final 500cc points table were Suzuki-mounted, including such illustrious privateer names as Agostini, Read and Lucchinelli, whose sponsors had to pay good money – though not a lot, considering the bike’s performance – to get their hands on what almost overnight had become the only way to go 500GP racing.

It would remain a competitive privateer option right up until the end of the production run in 1990, winning Suzuki seven consecutive 500GP Manufacturer’s World titles from 1976 to 1982, including four Riders crowns in 1976/77 with Barry Sheene on Heron-entered bikes, and two more on Team Gallina machines for Marco Lucchinelli in 1981, and Franco Uncini in 1982. Some record.

It would remain a competitive privateer option right up until the end of the production run in 1990, winning Suzuki seven consecutive 500GP Manufacturer’s World titles from 1976 to 1982, including four Riders crowns in 1976/77 with Barry Sheene on Heron-entered bikes, and two more on Team Gallina machines for Marco Lucchinelli in 1981, and Franco Uncini in 1982. Some record.

One man who didn’t have to dig into his pockets even a little to buy an RG was 1976 500cc World Champion Barry Sheene. By winning the first of his two back-to-back world titles on his factory Texaco Heron Suzuki, Barry underlined how dominant the new square-four had become, by winning five of the six GPs he rode in that year, finishing runner-up to teammate John Williams in the other one.

“Winning Suzuki seven consecutive 500GP Manufacturer’s World titles from 1976 to 1982, including four Riders crowns in 1976/77 with Barry Sheene on Heron-entered bikes”…

In the days when only a rider’s best six results counted towards the final points table, it was as near a perfect score as it’s possible to get, and confirmed Sheene’s unique status as a household name, who popularised bike racing in the eyes of Joe Public as nobody before – or sadly in Britain, anyway, since.

GROWING PAINS

If 1976 was Barry’s benchmark GP season, the year before had seen sporting success mixed with horror and hurt for Britain’s best. For in March 1975 Barry suffered his horrific 170mph Daytona crash when tyre-testing for the 200-miler on his F750 works Suzuki, sustaining injuries that for most other riders would have been as career-threatening as they were traumatic, including a broken thigh, wrist, arm, collarbone and six ribs, two cracked vertebrae, and much else.

“Measuring 56 x 50.5mm and broadly based on the extremely fast but equally fickle RZ63 250cc square-four GP racer of exactly ten years earlier”…

Yet such was Sheene’s resilience that a mere eight weeks later, he hobbled aboard the works XR14 Suzuki 500 square-four, and qualified sixth for the Austrian GP – though in spite of showing track officials a medical release, and demonstrating his ability to bump-start the bike on the grid, Barry wasn’t allowed to start the race. One week later at Hockenheim, for the German GP, he was and that’s when the countdown to the Cockney kid’s debut 500cc Grand Prix victory and Suzuki’s first, too, really began.

After countless World titles in the 50cc and 125cc tiddler classes in the previous decade, Suzuki had made its entry to the blue riband 500cc category with the twin-cylinder TR500, with which Jack Findlay scored the Japanese company’s debut 500GP victory in the 1971 Ulster GP, following it up two years later by winning the 1973 Isle of Man Senior TT. The following year, in 1974, the prototype XR14 rotary-valve square-four which two years later would spawn the RG500 customer bike, made its racing debut.

Jack Findlay scored the Japanese company’s debut 500GP victory in the 1971 Ulster GP…

Measuring 56 x 50.5mm and broadly based on the extremely fast but equally fickle RZ63 250cc square-four GP racer of exactly ten years earlier, whose appetite for seizing earnt it the chilly sobriquet of the ‘Whispering Death’, designer Makoto Hase’s new 500cc missile initially followed in its smaller-capacity ancestor’s tyre tracks in carving out a lurid reputation during 1974 as Hase and his R&D team struggled to match the bike’s undoubted performance with a semblance of reliability.

“A completely redesigned version of the XR14 was dispatched to Europe to be entered by the small works team of factory mechanics”.

In fact, the XR14 finished a close second first time out, in the 1974 French GP at Clermont-Ferrand, when Barry Sheene ended up just five seconds behind future world champion Phil Read’s MV Agusta at the flag, in spite of repeated plug oiling. But although this debut result flattered to deceive, as successive engine and handling problems blighted the bike’s development season, Suzuki had great hopes for 1975.

Read our other Alan Cathcart tests here…

A completely redesigned version of the XR14 was dispatched to Europe to be entered by the small works team of factory mechanics – one of each of the new bikes went to Sheene and Suzuki’s new recruit from Yamaha, Tepi Lansivuori, for them to race the whole season with, with two others shared between the favourite sons of various local importers, mainly Heron Suzuki’s Stan Woods and John Newbold, and Suzuki Italia’s Roberto Gallina and Armando Toracca.

Attached to the factory race team that year was Heron mechanic Martin Ogbourne, later to become Suzuki’s chief race engineer in a 15-year career with the works GP effort. He remembers the tribulations they suffered in making the XR14 competitive in its second season only too well. “There were two main problems,” Martyn recalls. “One was that cycle part technology was a long way behind the engine, so that getting the power to the ground – and there was lots of it – was a real problem.

“But secondly, for some unknown reason, the Japanese would set the engines up far too rich – they absolutely would not jet them down, presumably for fear of seizure. ‘

“And when an RG is too rich, to the rider it’s acting lean – it behaves exactly the opposite of what you’d expect”…

“And when an RG is too rich, to the rider it’s acting lean – it behaves exactly the opposite of what you’d expect. After the troubles of the previous year, the riders were extra fearful of a seizure, so we’d keep jetting them up and up, and the bikes kept getting slower – plug chops didn’t help, because it was the needle jet at fault. Stan Woods at Hockenheim flew past everything else on the track in a straight line, but in any of the chicanes it’d bog down and eight-stroke on the exit till it eventually cleared – or not, hence the plugs oiled repeatedly.

“It was only when we had a break after the first four races, during the TT, that we could finally go testing and sort out the problem. That’s when the bike started winning – when something else didn’t go wrong!”

Tubular steel double-cradle, Fabricated aluminium swingarm, Head Angle: 29°, Trail: 125mm, Wheelbase: 1395mm.

With Sheene still in hospital after Daytona, Lansivuori’s was the only works Suzuki square-four on the grid for the opening GP at Paul Ricard – but in pole position! The Finn led Yamaha-mounted Agostini, the eventual winner and defending world champion, by four seconds before his gear linkage broke, a cruel disappointment, but the rest of the field had been served notice of the square-four’s potential.

In the next round at Austria, with Sheene prevented from starting, Tepi finished a strong second to Kanaya’s works Yamaha on the fast, sweeping Salzburgring, following up a week later with third at Hockenheim. Sheene did start there, but retired after stopping for a change of plugs, with the gross over-jetting described by Ogbourne as the culprit. Woods soldiered on to finish 5th on an equally over-rich bike. At Imola the following week for the Italian GP, both Gallina and Woods suffered again from misfires, the Italian retiring with wet plugs and Woods eight-stroking his way to another fifth, one behind ex-MV rider Toracca, while Lansivuori non-started after breaking his collarbone in practice. Suzuki had flown in an updated new engine for Sheene, but a pawl broke inside the gearbox, leaving him stuck in gear, so he retired too.

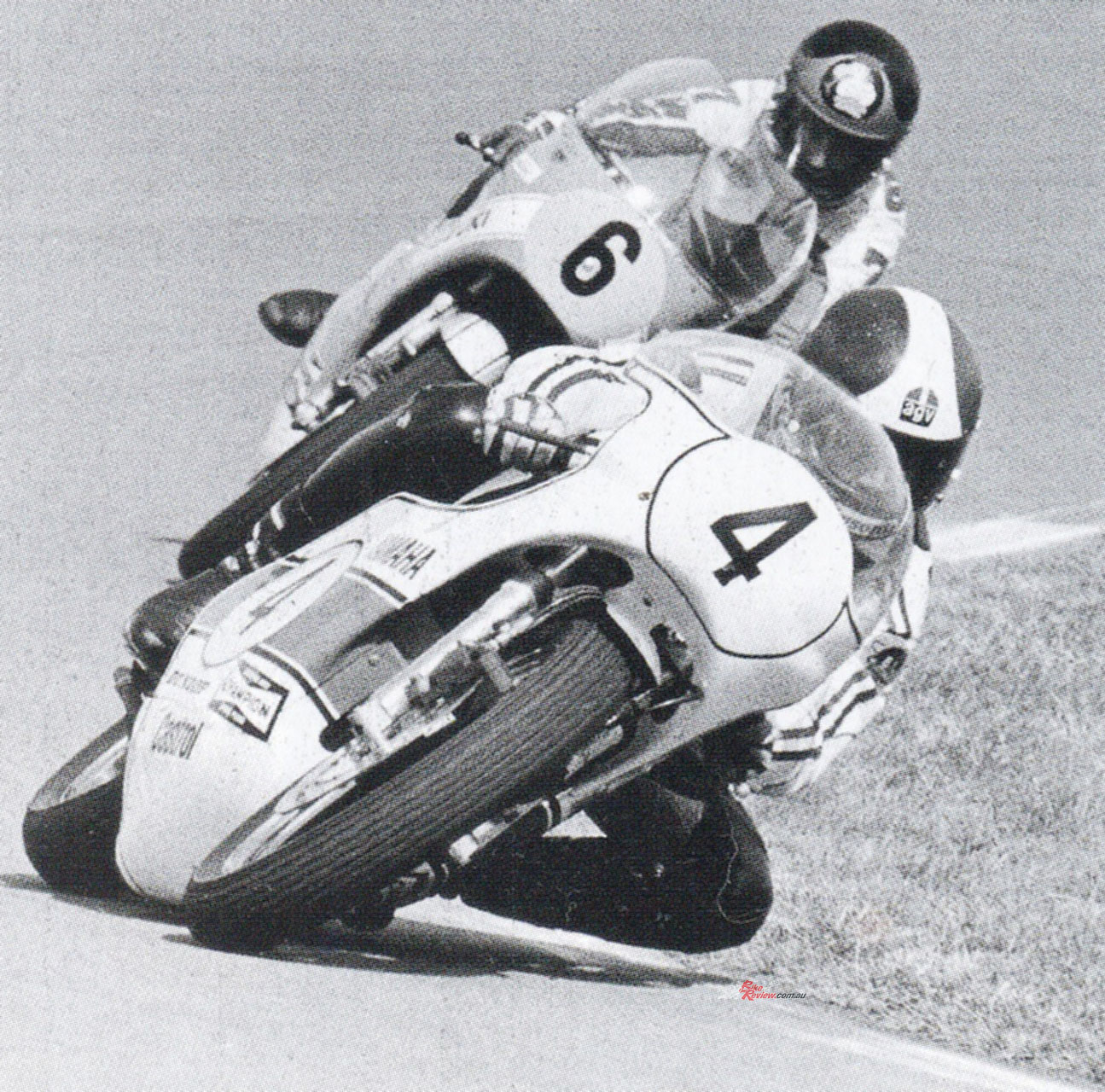

The five-week break before the Dutch GP at Assen enabled the Suzuki race team to turn the page on the XR14’s development – a step mainly linked to finding the right engine setup, rather than any mechanical improvement. The payoff came at Assen, when Sheene broke Agostini’s lap record in practice, to claim pole position, then spent the whole race apparently battling with the Italian maestro’s four-cylinder Yamaha, before cheekily sweeping past him round the outside of the last corner, to claim both his own and Suzuki’s first-ever 500cc four-cylinder GP victory by a wheel in a thrilling finish.

The payoff came at Assen, when Sheene broke Agostini’s lap record in practice, to claim pole position…

“It probably looked hectic, but the Suzuki had the edge, so I had it all under control,” Barry once told me in an interview. “I let him lead into the last lap, knowing I was much faster in the last two corners – where the chicane is today, only then it was a slow right hander, and the fast left before that. I’d passed Ago a couple of times up the inside of the last turn, trying to make him think that was where I’d try and come under him before the flag – but instead I swung wide, and as he looked inside I whistled round the outside and out-accelerated him to the flag. It was a fantastic race!”

Martyn Ogbourne, busy that day running an XR14 for John Newbold, who impressed by finishing fourth on his square-four debut, ahead of Lansivuori in fifth, remains convinced that this day marked Barry Sheene’s coming of age as a Grand Prix racer. “Barry could have won by a lot more,” he says, “but he wanted to show the world and especially the factories and other GP riders that he could out-think Ago and had the measure of him. It took a lot of balls even leaving it to the last lap to pass him, let alone the last bend, but it was a risk that paid off as he timed the move to perfection. After that, he was the one the others had to worry about beating, not Read or Ago or any of them.”

The truth of that was borne out just one week later at Spa, where Sheene qualified in pole position with a new lap record, a massive five seconds faster than reigning world champion Phil Read’s MV, and his teammate Bonera, with Agostini fourth. Barry was seven seconds faster than either of the other Suzuki riders, and though the wailing MVs took a decisive early lead, Sheene swiftly pegged them back and began stalking Read, planning to do the same number on him as on Ago at Assen. But the Suzuki had an achilles heel, “In those days the primary gear was still a bolt-up arrangement,” says Martyn Ogbourne, “and two laps from the end Barry felt the engine start to vibrate strongly when the bolts began to shear, and pulled into the pits before the transmission locked up. Very wise!”

Read won, Lansivuori seized, but John Newbold finished second on his first visit to Spa – some achievement, though sadly it was the last time ‘Noddy’ would race the XR14. Sheene and Suzuki had some consolation though, Barry’s new lap record set in the race at 135.75 mph still stands today as the fastest-ever lap in any Grand Prix race – anytime, anyplace.

Barry’s new lap record set in the race at 135.75 mph still stands today as the fastest-ever lap in any Grand Prix race – anytime, anyplace…

Suzuki’s response to the failure couldn’t be faulted. Just two weeks later, at the Swedish GP at Anderstorp, Sheene qualified on pole with a new one-piece primary shaft made from a solid billet fitted to his engine which had been flown in from Japan, going on to blitz the field in the race, which he won easily, though Lansivuori crashed again. The Finn made up for this by finishing second on home ground at Imatra the following week, where Sheene retired with his engine misfiring through being set up too rich – must have been the forests which fooled them!

In the final race of the season at Brno, it was Tepi’s turn to take pole ahead of Sheene, but in the race the Suzuki riders had to grapple with the extra weight and bulk of a nine-gallon/41-litre fuel load, necessitated by the organisers’ decision to run an extra-long 115-mile race on the fast public roads.

To make matters worse, the FIM jury banned the use of slick tyres at 8am on race morning after early rain – even though the sun was shining brightly later, hours before the race! In spite of this handicap, Sheene battled with Read (whose four-stroke MV needed less fuel) for the lead in the first few laps, before retiring with a rumbling engine. Lansivuori took up the challenge, but retired on the last lap with a broken clutch, and Toracca dropped out early on. It was a lowkey finale to Suzuki’s breakthrough season, in which Lansivuori finished fourth in the World Championship and Sheene sixth, with Suzuki third in the manufacturers series.’

It was however a season, which had laid the ground in fine style for the advent of the RG500 Mark 1 a few months later, a bike that was in every way a close replica of the 1975 XR14 works racer – as well as for Suzuki’s shock decision to withdraw from racing as a factory team, instead entrusting their official Grand Prix race operation to Heron Suzuki.

A NEW YEAR

Sheene dominated the 1976 World Championship with a new 54 x 54mm version of the XR14, known as the RG500A thanks to the A-shaped subframe behind the seat, and fitted with seven-port barrels instead of the five-port cylinders of the 1975 XR14s, which Heron continued to enter for their second-string riders. These were still good enough to propel Sheene’s John-Boy teammates Williams (Spa) and Newbold (Brno) to Grand Prix victory, as Suzuki won their first 500cc riders and manufacturers GP titles. Though the RG350 which Martyn Ogbourne asserts was drawn up but never built, and the RG750 which did apparently run on the dyno in prototype form, and would have blitzed the TZ750 if Suzuki and the tyre companies had found a way of putting more than 150bhp to the ground, were spinoff projects that did not materialise, the 135bhp 652cc XR23 version built for the Imola and Ricard 200-milers, on which Sheene won the 1977 British Superbike title, did. That 1975 Assen victory was the first of many for the square-four Suzuki, and a watershed moment in 500cc Grand Prix history. Mission accomplished.

RIDING THE SHEENE SUZUKI

The mean-looking quartet of smoke-spitting stingers rasped their sharp, trademark crackle across the Montlhery paddock, accompanied by the distinctive rattle of the XR14’s rotary valves as Nigel Everett dropped the clutch, and the Sheene Suzuki burst swiftly into song. As redolent of racing in the 1970s as an open megga mounted on a Manx Norton is of the previous decade, just watching and listening to the sound as he warmed it up provided a stirring trip down memory lane, to the final year that Grand Prix bikes raced without silencers. 1975, the year that this very bike I was about to ride delivered Suzuki its first-ever four-cylinder 500cc GP win.

“just watching and listening to the sound as he warmed it up provided a stirring trip down memory lane”.

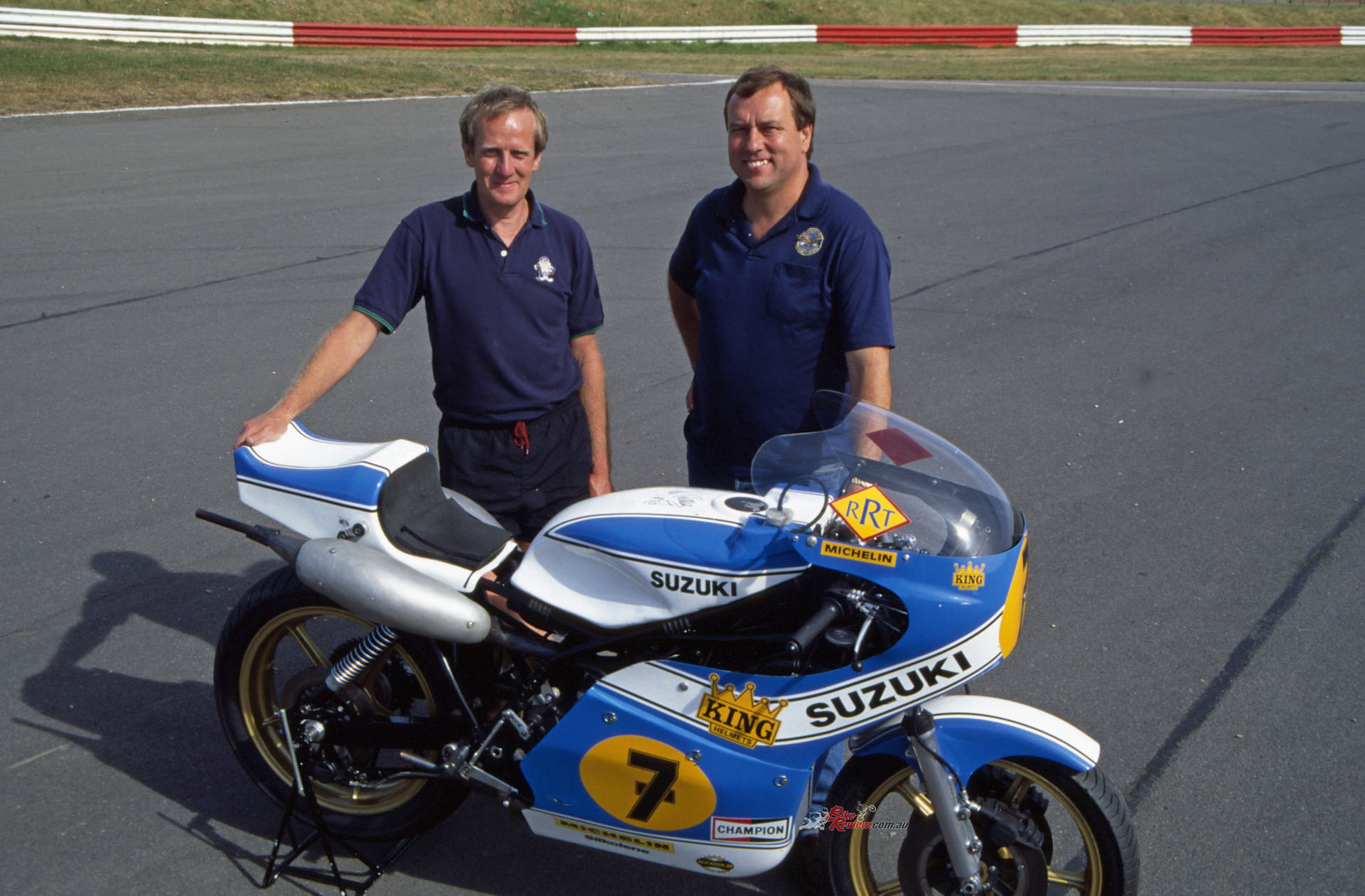

Owning an ex-works Japanese GP racer is the dream of many but the good fortune of just a few – but in this life, you make your own luck and British enthusiast Chris Wilson’s superb collection of factory 500cc two-strokes has been built up over the past few years thanks to his determination to preserve the often unconsidered GP heritage of the ’70s and ’80s post-Classic era.

“The roots of the wonderful technology we see in Grand Prix racing today are often taken for granted,” says Chris, “and in seeking to preserve them, it’s been surprising how many wonderful bikes have turned up in a very sorry state, having been just slung in a corner and forgotten.

To begin with, the Suzuki is extremely easy to fire up, as befits a bike built in the push-start GP era, when I’m sure the XR14 riders would have been one of the first to hit the front.

“We’ve been able to track down several of them and Nigel Everett’s Racing Restorations operation has brought them superbly back to life. My overriding philosophy is to restore my bikes to original, authentic, trackworthy condition, then get them ridden in something approaching anger by people who know how. That’s why you’re here at Montlhéry, standing in for Mr. Sheene!”

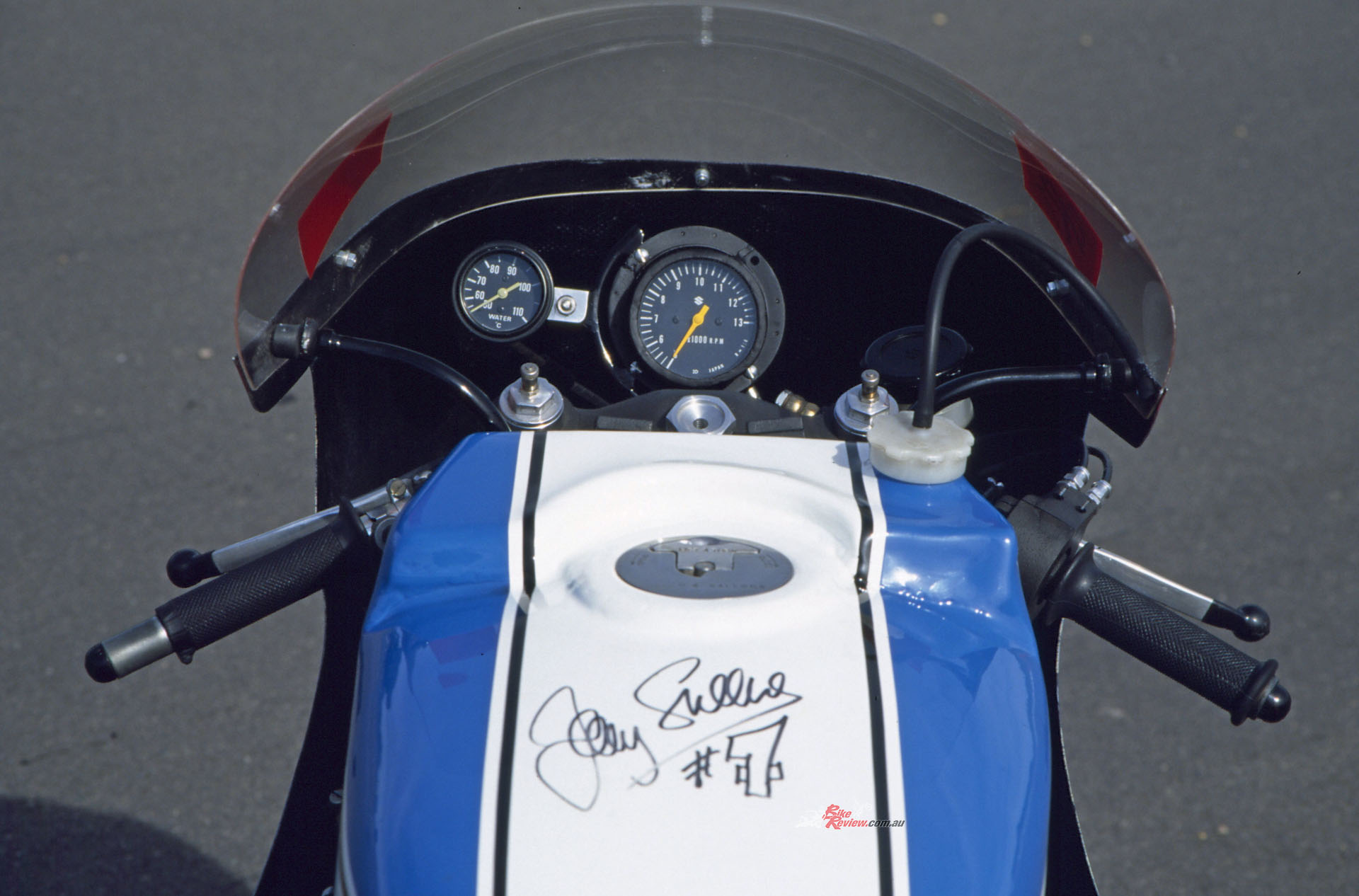

Sorry, only a pale imitation, I’m afraid – but if you were one of the fortunate thousands at the Assen Centennial meeting in May 1998, you’ll have seen Barry himself riding the same blue-and-white machine, aboard which he’d opened his 500cc GP victory roster 23 years before, on the very same track. A bike of initially indeterminate heritage, which Chris Wilson had acquired as a box of not very large bits, only to discover from the Heron race records held by George Beale that it was indeed Sheene’s 1975 machine and thus his Dutch GP winner, with chassis G56-1026.

Barry himself was sceptical, believing no ’75 works bikes had survived the crusher, but after Nigel Everett – himself a works Suzuki GP mechanic from ’82 onwards, – had sourced the parts to rebuild the Suzuki to race-ready condition, Sheene confirmed when he rode the bike at Assen it was indeed his, and even signed the top of the fuel tank to confirm this.

Sheene confirmed when he rode the bike at Assen it was indeed his, and even signed the top of the fuel tank to confirm this… He still described it as a ‘heap of junk’, though”…

He still described it as a ‘heap of junk’, though, after being blown off in the Centennial ‘race’ by Mamola and Hartog on much later Suzukis with up to 40 per cent more power – but, once a racer…

Still, by the standards of 1975, the XR14 Suzuki opened a window on a brave new world, just five years after Seeley G50-mounted privateers had been regular visitors to GP rostrums, the XR14 was the first 500cc GP racer to deliver over 100bhp at the rear wheel (101bhp at 11200rpm on the Everett dyno, running on 30:1 Avgas/Silkolene premix) or twice as much as the British singles, resulting in a 175mph top speed that was 35mph faster than they could manage.

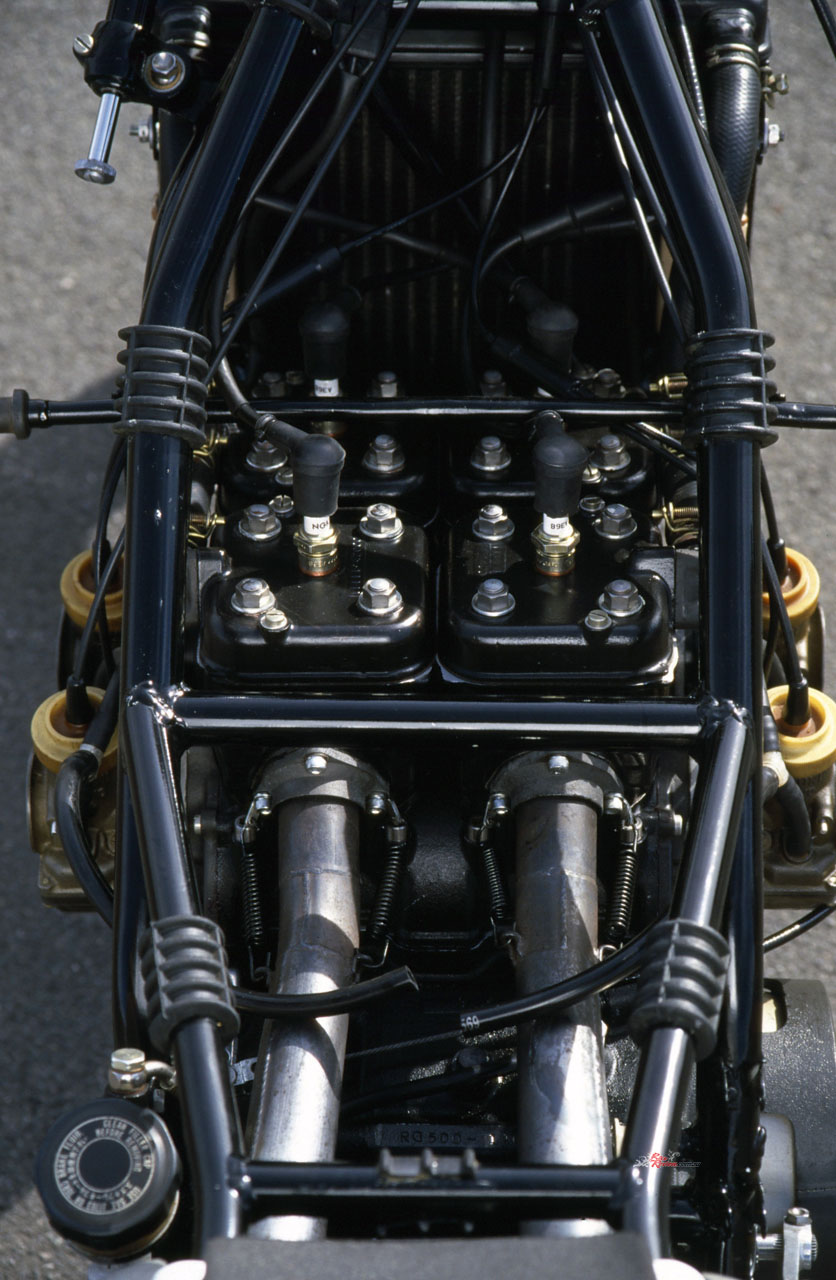

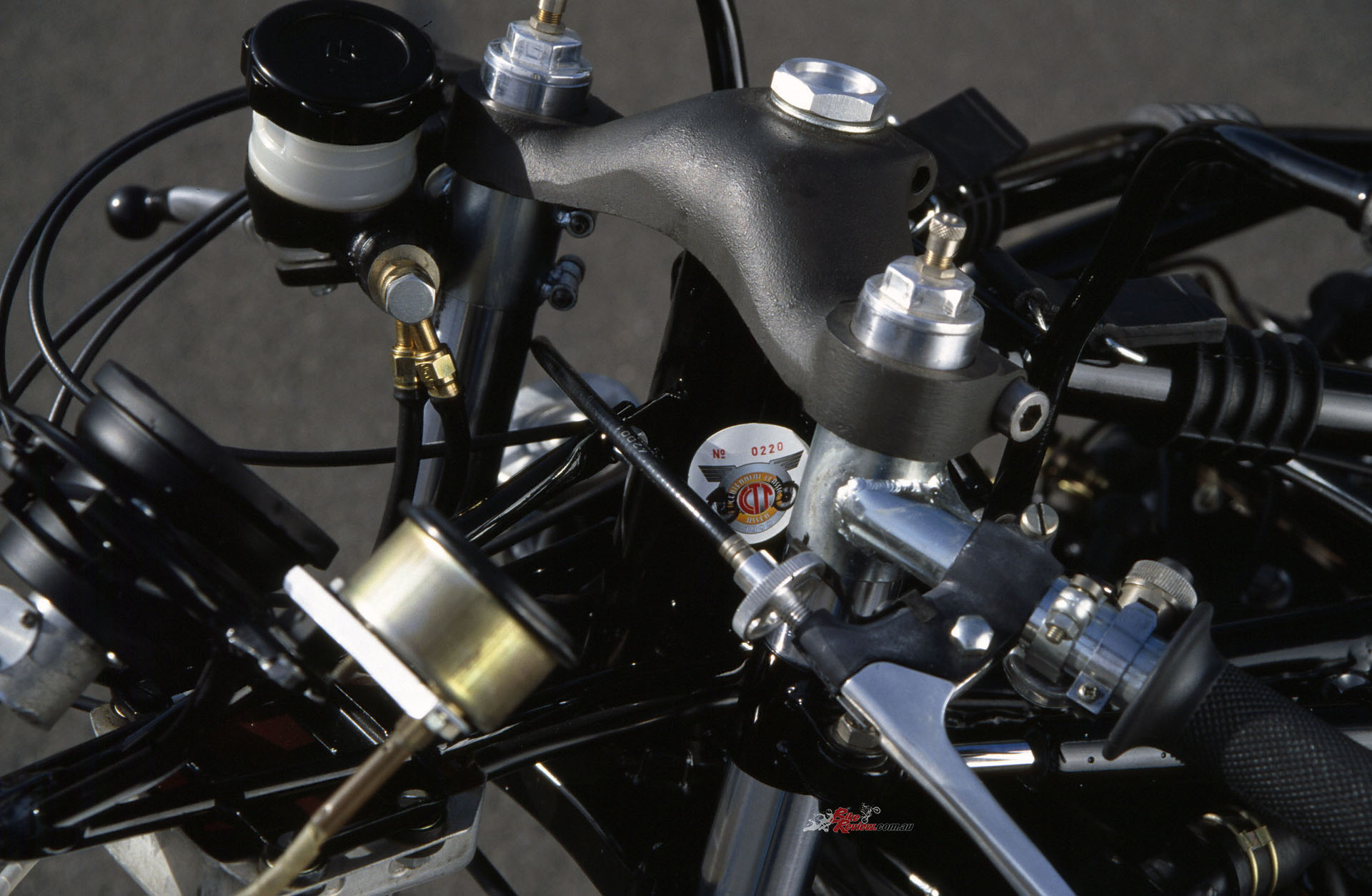

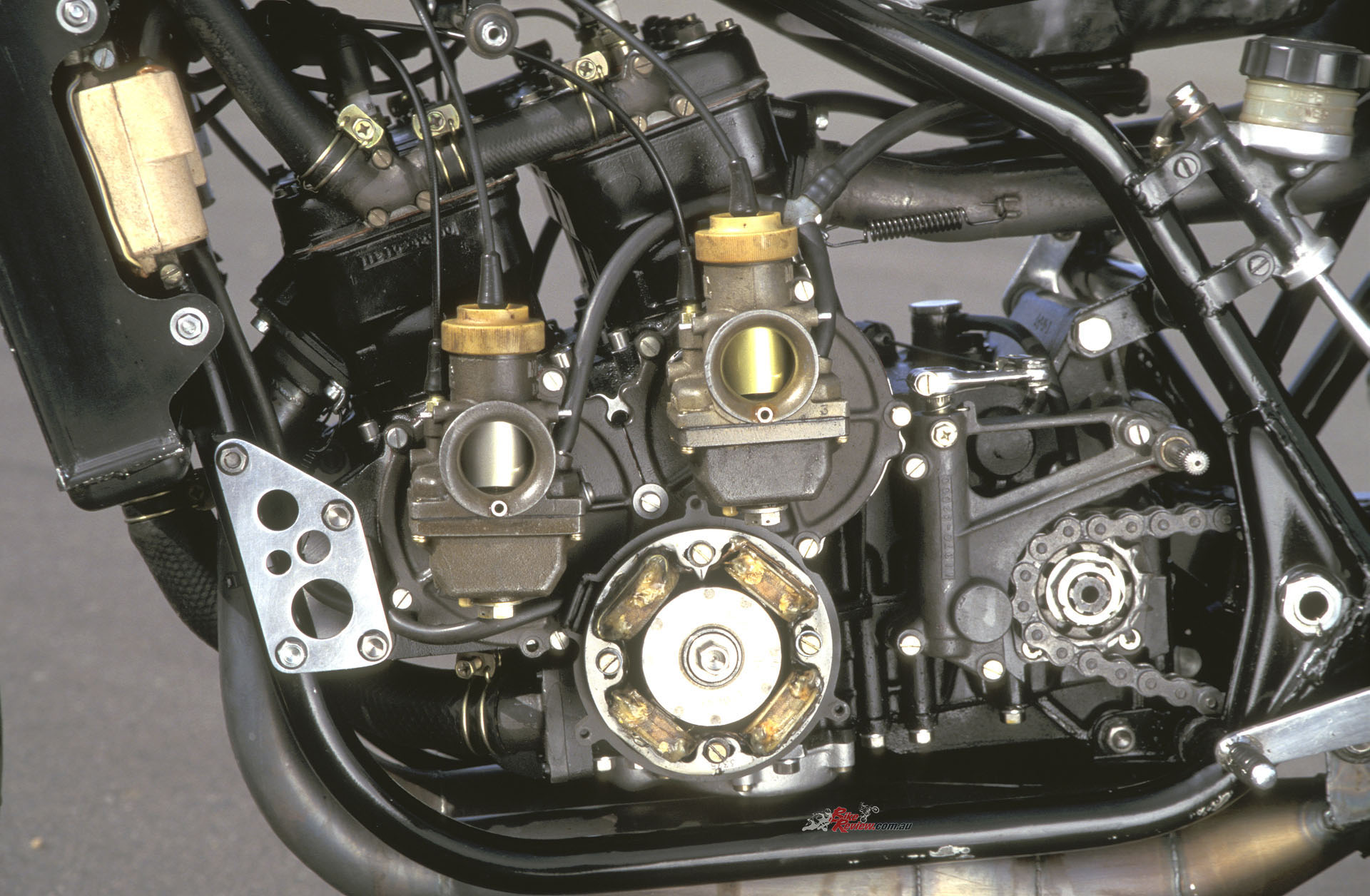

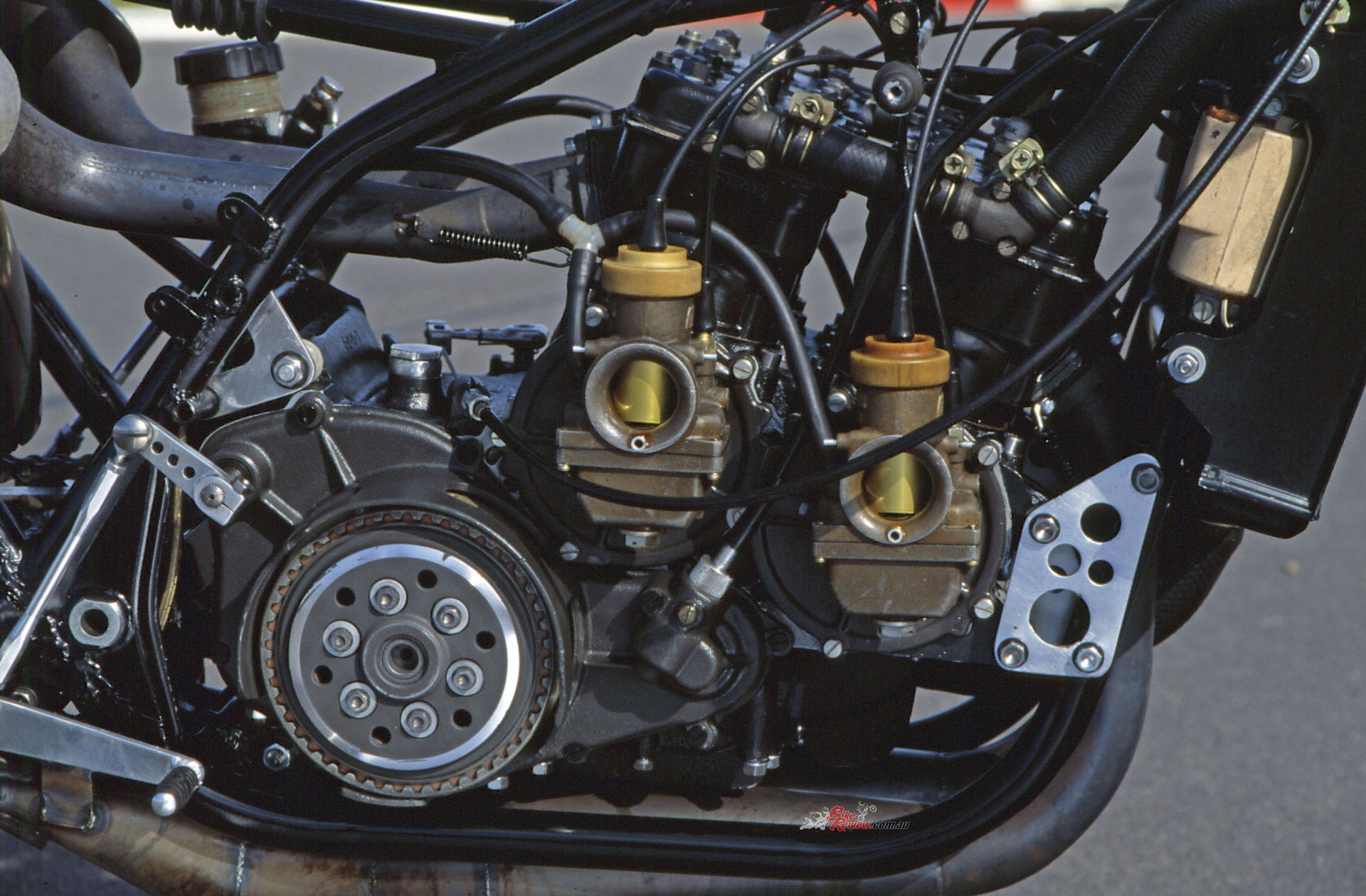

Though other XR14s used lighter magnesium crankcases, problems with the porosity of these persuaded Sheene to insist that his bike used heavier but more robust aluminium ones like those fitted here, with four separate cranks on the 56 x 50.5mm square-four rotary-valve configuration, individually geared to a primary pinion under the cylinders.

Though other XR14s used lighter magnesium crankcases, problems with the porosity of these persuaded Sheene to insist that his bike used heavier but more robust aluminium ones.

These were arranged in a flat square, angled slightly forward – the later, stepped-cylinder, twin-crank version of the RG500 was only adopted later (from the 652cc XR23 onwards), to provide space for a cassette transmission, with a raised idler gear. A pair of 34mm Mikuni magnesium-bodied carbs is mounted on either side to feed the rotary valves splined to the cranks, and the five-port cylinders (four transfers, plus a booster port aligned with a window in the piston skirt) have steel liners – chrome bores were still in the experimental stage back in 1975, and kept flaking off, recalls Martyn Ogbourne, so Sheene rejected them for his bike. There’s a single bridged exhaust port that’s responsible for the harsh crack to the Suzuki’s engine note, whereas Yamaha’s rounder porting of the era produced a much softer, muted sound.

But while the XR14’s potent square-four powerplant hastened the end of the four-stroke GP era, its chassis was firmly rooted in the past, with a relatively flimsy twin-loop tubular steel frame equipped with twin shocks (Hagons on this restored bike, Kayabas in the era) and 35mm Kayaba forks, with adjustment restricted to changing the oil or altering the air-damping pressure. Head angle is a kicked-out 29 degrees, trail an equally humungous 125mm, though at 1395mm the wheelbase is quite compact, and the 135kg half-dry weight more than respectable, thanks in part to the profusion of titanium fasteners, each with their heads patiently scalloped out.

Sheene’s preferred Campagnolo cast wheels are fitted with skinny 18in Avon tyres kindly donated by the British firm, who were happy to let Wilson retain the Michelin stickers on the bike’s fairing, which is exactly as Barry used to race it. An authentic restoration, which is a credit to Everett’s handiwork.

Which is why when Chris Wilson asked me to join Jean-François Baldé aboard the Wilson Kawasaki KR500, and Marc Fontan on Chris’s works 1983 Yamaha, to ride the XR14 Suzuki in a quartet of demos in front of 30,000 spectators at France’s annual Coupes Moto Legende meeting at Montlhéry, I didn’t need asking twice.

I do have a self-interestedly cautious approach to track testing period two-strokes, on the grounds that these can cause pain and hurt if not perfectly prepared, and properly set up. With Nigel Everett in charge of the Wilson bikes, though, there were no such concerns –my only problem was to figure out how to contend with what I expected would be a very sudden power delivery, typical of rotary-valve race engines and on treaded tyres, too!

I needn’t have worried. To begin with, the Suzuki is extremely easy to fire up, as befits a bike built in the push-start GP era, when I’m sure the XR14 riders would have been one of the first to hit the front. Three steps, drop the clutch, catch it on the throttle and pump the gas like mad to make it pick up – then hop aboard (taking care to clamber well over the high-set seat), and take off. Almost literally – wheelies are all too easy and spectacular from a push start on a bike this powerful. Snuggle aboard, and discover you’re sitting inside the bike rather than perched atop it, with the wide fairing dictated by the rotary-valve configuration giving good protection for knees and body, surmounted by a fairly tall screen that’s easy to tuck behind. Footrests are quite high-set, but while the fat expansion chambers either side of the seat don’t get in your way when tucked aboard, they do make it hard to hang off unduly going round turns, perhaps leading to the distinctive, upright, knee-out Sheene riding posture.

Having clambered aboard you’re now making friends with the Suzuki’s real trump card, that amazing engine. Compared to what else was around at the time, the XR14 RG500 was clearly a big step forward, especially in terms of its explosive acceleration, that would have taken riders unused to such power a while to come to terms with, and exploit. Below 8000rpm there’s effectively no usable power, so the trick is to wind it up on the clutch to coax it into the powerband exiting a slower corner but only once you’ve made the turn and have the bike more or less upright – then hold on tight as the tacho needle builds numbers pretty fast, and you’ve hit the 11200rpm power peak.

“There’s precious little overrev, so rather than fall off the pipe you need to change up, via the right-foot one-up gearchange conversion that Sheene fitted to all his bikes”…

There’s precious little overrev, so rather than fall off the pipe you need to change up, via the right-foot one-up gearchange conversion that Sheene fitted to all his bikes. Though slightly notchy, the gearshift is quite fast and very precise, so you can just flutter the exhaust note an octave changing up through the top four gears in the six-speed cluster, which are all very close together to keep the Suzuki on the move. But you need to stretch the revs to keep the engine on the boil in the bottom two changes, because if you don’t the wide gap in ratios will let you fall out of the power band and bog the engine. When that happens, it’s better to change down a gear if you can and get the engine singing again rather than clutch it, because that gets it back on the pipe quicker.

“It rockets out of a turn like the trio of Montlhéry chicanes with the front wheel pawing the air in third gear, with the raucous engine note rasping in your ear – earplugs are definitely a good thing when riding this bike!”

But when you do, the Suzuki’s acceleration is awe-inspiring by the standards of the era, and pretty impressive even today. It rockets out of a turn like the trio of Montlhéry chicanes with the front wheel pawing the air in third gear, with the raucous engine note rasping in your ear – earplugs are definitely a good thing when riding this bike! And though the forks feel really wooden and flimsy, the rear suspension’s laydown shocks, set at a 45-degree angle, are reasonably compliant, enough to let you fire the XR14 up out of a turn on a bit of an angle, though not too much on such skinny tyres, even with the ace grip of the Avon rubber.

101bhp at the rear wheel on a bike weighing 135kg rewrote the book on power to weight ratios of the era, and even today it’s impressive – though you can feel the frame flexing and twisting beneath you as you get hard on the gas.

101bhp at the rear wheel on a bike weighing 135kg rewrote the book on power to weight ratios of the era.

“Nothing was ever strong enough handling-wise on the RG500,” said Barry Sheene to me when we bench raced later about his bike. “The frame, forks and swingarm all needed beefing up – the Japanese should have started working on beam frames and bigger forks long before they did.” But they didn’t, and the result is a compromise which, provided you ride it in the way it was designed to be used, as a point ‘n’ squirt machine, does its job OK. The twin-shock rear end is pretty stiff, though damping is OK by the standards of such a layout, it still bounces over bumps pretty horrifically, especially on the concrete Montlhéry bankings.

There you have to take your courage in both hands and just let the Suzuki leap and lurch about, flapping the bars occasionally in your hands for an instant, but all strangely enough without getting out of hand – uncannily, it just sorts itself out, and all the quicker if you keep it wound on. Still, handling is adequate rather than exceptional, leaving you to take advantage of that hundred-plus horsepower to brake long and deep into the apex of a turn, then turn the bike round and fire it out. No wonder Sheene outdragged Ago’s works Yamaha to the line at Assen.

Riding the bike in this way on a crowded track is an acquired skill that places a premium on luck, especially with slower backmarkers crowding you out in turns, or wandering over the track and getting in the way of a much faster bike. The reason is the huge progress in braking performance made over the past 25 years since the Suzuki was built, and especially brakes like these that were made in Japan. Originally, the 1975 XR14 was fitted with smaller, lighter plasma-sprayed alloy discs in order to try to reduce the gyroscopic effect of the brakes on the steering, but Sheene didn’t like these and opted for these bigger 290mm stainless steel discs, bolted rigidly to the carriers and gripped by two-piston Tokico calipers. Even by the standards of the drum brakes these had supplanted, their performance is pathetic, and frankly dangerous. There’s absolutely no bite, and only nominal stopping power – though at least they don’t fade, because they never worked properly in the first place!

“The brakes were horrendous,” agrees Martyn Ogbourne. “They looked very nice and never rusted – but that’s because they had a high percentage of stainless steel in them, which apart from having no bite also reflected the heat back straight into the pads. The problem was that they couldn’t and maybe still can’t make the right grade of cast iron in Japan, and of course using Brembos or Lockheeds at the time was a Not Made Here no-no. It was easily the worst feature on the bike.”

I couldn’t agree more and to stop from speed you can’t ride it like a two-stroke and do all your braking late and hard, zapping down through the gearbox all in one go as you slow for the turn. Here on the Suzuki you have to use the surprising degree of engine braking in the lower gears to stop, using lots of revs on the overrun in the lowest three ratios, and standing on the reasonably effective 270mm ventilated rear disc, which Nigel says weighs quite a bit more than either of the front discs, at least does make the bike stop a little better. Phew! And of course, when that happens you don’t want slower riders in front of you, because you have no margin for error. Better to plan ahead and try to think your way past them, if you can.

In one of my battles with other period two-strokes in action at Montlhéry, I had a great dust-up with the Offenstadt Kawasaki 750 monocoque of the same era, with the 500 Suzuki almost identical on top speed, better on acceleration, but not nearly so good on the brakes as the French machine. However, by the last time we took to the track on Sunday afternoon, I thought I had riding the XR sussed – so when I passed Jean-François Baldé on Chris’s KR750 to take the ‘lead’ in the ‘race’, it seemed to be all coming together. Though he could easily have repassed me on the faster, later bike, Jean-Francois obligingly tucked in behind so we could stage a pretend battle for the benefit of the large crowd. Only – next time around, running down to the first turn flat out in top gear, I felt the rear end start to slide around beneath me in a straight line, so backed off the gas just as JFB shot past me, gesticulating madly to slow down. I tiptoed round the tight first turn, and as I did so got a big slide from the rear. No, not a flat tyre but oil all over it. Who says two-strokes are so PC?!

“How Barry Sheene could have competed with it successfully enough to finish second in the 1975 British Championship speaks volumes for his skill and bravery”…

Back at the pits, Nigel confirmed that a sleeve gear had broken a dog and spat it out the back of the gearbox casing, together with the oil. Play for that day was over but a couple of months later I was summoned to Mallory Park to run the bike in again for Chris, after an engine rebuild which including replacing the gears in question, and welding up the casing.

After the wide open spaces of Montlhéry, riding the Suzuki on a tight British short circuit was a real eye-opener – how Barry Sheene could have competed with it successfully enough to finish second in the 1975 British Championship speaks volumes for his skill and bravery. The lack of brakes is the most worrying factor, especially somewhere like Mallory with a hard stop at the hairpin each lap, but the relatively narrow powerband and wide gaps between the bottom three gears also make riding the Suzuki even just a fraction as fast as I did in France, a real test of skill which I’d need a lot more practice to master. Though relatively tall, the XR14 steers quite well, it’s only the flimsiness of the frame that lets the bike down, as again you feel it flexing running over the bumps at Devils Elbow on the power. Still a great-sounding bike, though and what good power up high.

Chris Wilson’s dedication and Nigel Everett’s expertise have certainly helped preserve a unique piece of road racing history in completely authentic guise – the bike that scored the first-ever Grand Prix race victory of the Manx Norton of the two-stroke era.

SPECIFICATIONS 1975 SUZUKI RG500 XR14

ENGINE: Water-cooled, rotary-valve square-four, two-stroke, 56 x 50.5mm bore x stroke, 497cc, 8:1 compression, four 34mm Mikuni magnesium-body VM34SS carbs, Nippondenso CDI ignition, six-speed, multi-plate dry clutch.

CHASSIS: Tubular steel double-cradle, Fabricated aluminium swingarm, Head Angle: 29°, Trail: 125mm, Wheelbase: 1395mm SUSPENSION: 35mm Kayaba adjustable air-damped telescopic forks, dual Hagon shocks BRAKES: Dual 290mm Suzuki steel rotors with two-piston Tokico calipers, single rear 250mm Suzuki ventilated steel rotor with two-piston Tokico caliper WHEELS & TYRES: Campagnolo cast aluminium wheels, (F) 110/80-18 Avon AM22 on 3.25in, (R) 150/70-18 Avon AM23 on 3.50in

PERFORMANCE: TOP SPEED: 284km/h(175mph), POWER: 101bhp at 11200 rpm (at rear wheel) WEIGHT: 135kg, wet without fuel

OWNER: Chris Wilson, Broadstairs, Kent