With WDW2024 a massive success this week, we had to take you back in time to one of the most iconic eras of all Ducati superbikes, the 996... Photos: Kel Edge/Guus van Goethem

Quite apart from its domination of MotoGP, the past two years have seen Ducati rule the World Superbike series once again with the Panigale V4 R, its MotoGP racer-with-lights ridden to successive title wins by Alvaro Bautista. Almost 30-years ago, it was the 996…

But 2022 came after the Italian company saw an entire decade pass without championship success in either the Riders or the Manufacturers titles, in between Carlos Checa’s brave privateer win in 2011 on the Team Althea 1098R (read Jeff’s test of that bike here) – the final WSBK title victory for a V-twin – and the first of Bautista’s brace of crowns two years ago. Checa’s against-the-odds title success was in every way the end of an era.

Fear of a similar landmark page-turning moment had already come once for fans of the desmo V-twins in the year that WSBK clocked up its tenth birthday back in 1997, when Ducati’s run of three successive World Superbike Riders titles (and six in the previous seven years), plus seven straight Manufacturers crowns, was broken at last by Honda, who won both titles with the Castrol-sponsored RC45 V4, with John Kocinski claiming the title after making the move the previous winter away from Ducati.

Read our other Throwback Thursday articles here…

After more than half a decade of Superbike supremacy for the Italian firm, punctuated by a solitary title for Kawasaki courtesy of Scott Russell in 1993, the balance of power in top-class four-stroke racing seemed perhaps be shifting away from the Italian marque’s V-twins. Was the party perhaps over for the bikes from Bologna?

“Six-time winner Fogarty and his fellow works Ducati rider Frankie Chili, 7th in the final standings, had won nine races between them on the desmo V-twins”…

Well, maybe it was no coincidence that 1997 was the first year Ducati couldn’t bump up the capacity of its trademark 90° V-twin motors compared to the previous season, to try to keep pace with its Japanese rivals. Mind you, they didn’t lose the title for want of trying. For the best part of the season Carl Fogarty, Ducati’s prodigal son, was in contention for the championship in his comeback season on the Italian V-twin on which he’d won two World titles in 1994/95, after an away year with Honda riding the V4 that would ironically wrest the title from his clutches – doubly ironically, ridden by the man Carl swapped seats with, John Kocinski.

At the halfway mark in the 12-round/24-race series, Fogarty had held the points lead, having never finished lower than fourth in any race. But then it all went awfully wrong, as consistent Carl became a crasher, sliding out of contention no less than five times in total during the second half of the season, to hand Kocinski the title on a bed of gravel.

“To be completely honest, up till then I’d taken Foggy’s well-publicised complaints about the V-twin’s handling with a pinch of salt”…

Never mind that six-time winner Fogarty and his fellow works Ducati rider Frankie Chili, 7th in the final standings, had won nine races between them on the desmo V-twins, same as Kocinski (plus another three victories for his Honda teammate Aaron Slight). For sure it had been on the cards for a couple of years that Honda would get the measure of its Italian rival sooner or later, and now it had happened. The timing couldn’t have been worse, either, from the point of view of the company’s new owners, the American TPG investors group, for this was their first full year in the Ducati drivers’ seat….

But was it that the Hondas had got better, or the Ducatis worse – or maybe a bit of both? Only one way to find out, by comparison-testing the bikes of Fogarty and Chili on exactly the same Assen track where one year earlier I’d done the same with the similar V-twin desmos of that year’s World Superbike champion Troy Corser, and John Kocinski. So the day after the Carl ‘n’ Frankie road show had avenged their defeat by Kocinski and Honda in Race One on the Dutch track by cruising to an untroubled 1-2 victory in Race Two, the Virginio Ferrari and Team Gatalone squads fronted up their two works desmos in pit lane, for me to compare and contrast 1997’s strongest weapons in the twin-cylinder Superbike armoury. Tough job, right?!

Well, actually – yes, when the bike in question was as hard to handle and as downright unruly as the Fogarty Duke I sampled first, after a 20-lap warm-up aboard Carl’s mate Jamie Whitham’s works Suzuki GSX-R750. To be completely honest, up till then I’d taken Foggy’s well-publicised complaints about the V-twin’s handling with a pinch of salt, figuring he needed time to re-attune himself to riding a twin after that year away with Honda. But it was also worth remembering how big a step up there’d been in the power of the 996cc motor when I’d ridden the Ducati the previous year, compared to the user-friendly pussycat performance of the ’95 season’s 955cc desmo that Carl had won his second World title with.

It was a bit like squeezing two years of development into just one, as far as he was concerned. A year earlier, I’d marvelled at the feat of Ducati’s development engineers in producing a big-bore motor that actually revved higher and pulled harder than the smaller, older engine. It was more like a two-stroke desmo GP racer than the trad-style turbo tractor all previous Ducatis had been, with their meaty midrange, torquey traction and power to go all through the rev range. The new ’96 bike was a peakier revhound, instead of a super-slugger, and you were encouraged to ride it accordingly. Maybe the ’97 bike was the same, only more so. Was Carl having trouble adjusting to it?

Well, no – but I was! After one slow lap to settle in, exiting the Assen chicane at around 6,000 rpm, I cracked the throttle wide open as soon as I was pointed in more or less the right direction, and – well, not much happened. Then, as the revs mounted rather slowly, the Ducati cleared its throat just over 7,000 rpm and the power came in fiercely, sending me rocketing off down pit straight as the digital tacho built numbers like Concorde’s altimeter on takeoff. Suddenly, it’s reading 12,300 revs and it’s time to change up by tapping the KLS powershifter with its trademark ultra-sensitive Foggy setting, to score a higher gear. Acceleration was awesome by my real-world standards – hard to believe the Honda was even quicker off the mark, as I’d confirm it was riding by Kocinski’s World champion RC45 the day after he clinched the title in Indonesia.

But still – the ’97 Ducati did take time to get going from low down, not like last year. OK – I get it: 12 months of development equals more power, but up high – gotta use more revs, so try harder to keep up turn speed, and use one gear lower. Next time round, flip from one side to another in the chicane again (noticing as I did so that it seemed harder to make the V-twin change direction than I recalled from before), gas it up hard and – whoa! What happened?? Did someone light the afterburner? I’d never before got such instant pickup from a four-stroke V-twin. I knew this engine was fuel injected, and so throttle response was sharper and crisper – but I’d been racing such bikes for the past eight years, so I knew what to expect. And this wasn’t it…

Alan literally having to fight the Fogarty bike as the abrupt power kicks in and the rear tyre breaks loose.

Especially when the payoff for this sudden blitz of beefy power was a wobble and a weave as the rear suspension pogoed up and down, while I was slightly leaned over for the right-hand curve before the finish line and had hit the little dip in the road surface when leaving the chicane hard on the gas. Or again exiting the first turn on the Assen National circuit we were using, when you hit the ridge in the road surface where it rejoined the GP circuit while you’re cranked hard over, just as you’re getting feeding the power in hard.

“Did someone light the afterburner? I’d never before got such instant pickup from a four-stroke V-twin”…

Sorry, but I didn’t like power-sliding in off-camber turns with the bike doing the shimmy-shimmy shake-shake! I hadn’t had a Ducati do this to me since back at the very beginning of 916 development in 1993, before Massimo Tamburini sorted out the handling in mid-’94, mainly by extending the swingarm 25mm. Even the ‘96 desmo two-stroke didn’t behave like this: must be the rear shock, too soft for my extra weight. Let’s stop and fix it – Carl can’t be riding it all the time like this.

“Yes, I’m afraid he does,” said Foggy’s race engineer Tony ‘Slick’ Bass apologetically. “You’ve just had a firsthand experience of what Carl’s been up against all season, and whatever we’ve done to try to fix it, the problem’s still there. We might make it a little better for you by changing to a harder rear spring, but we can’t dial it out. Sorry!” Well, OK – let’s go back out there again, and try to analyse this. The fierce power delivery delivered impressive acceleration once hooked up right, but the problem came when I shut the throttle under braking, trail-braked into a turn, then opened the throttle again hard while still cranked over.

If I stopped trail-braking and tried to brake only in a straight line, then entered the turn with the throttle already part-open, it seemed to prime the gas and didn’t make for such a fierce pickup. Took practice, though – and anyway, riding like that is OK by yourself, but trying to outbrake someone in the heat of a race, then remembering to watch out for the muscular mega-torque on the way out of the turn you’ve just taken the lead into, would be another matter. And the yumping suspension response still wouldn’t go away. Hmmm.

“The problem came when I shut the throttle under braking, trail-braked into a turn, then opened the throttle again hard”…

“I knew straight away at the start of the season something was wrong, but I weren’t sure what,” said Carl Fogarty to me at the next WSBK round in Albacete, where with two DNFs against the Honda/Kocinski duo’s pair of wins he had his worst weekend of an already troubled season. “The biggest problem is acceleration. It doesn’t want to pull out of turns, so you drop the gearing – but then it’s wrong for other corners, which is why at every circuit, I’ve struggled to get the overall gearing right. There’s a big hole at the bottom of the power band, so it doesn’t kick in till much later on – but when it does, it comes in very fiercely. This makes it very hard to ride in the turns, so I keep running wide all the time, like I’m in the wrong gear.

“I knew straight away at the start of the season something was wrong, but I weren’t sure what,” said Carl Fogarty…

That was my main complaint with the chassis, not holding a proper line – I’ve tried countering that by going in wide and leaning over more, but then I lose edge grip on the tyre, and I’ve even fallen off doing that. Same thing if I use one gear lower, then you lose grip, and – watch out, or you’re on your ear. Then because the gearing’s wrong, once the tyre goes and the gearing’s a little bit tall, it starts pogoing the rear shock and upsetting the bike, like happened to you. And it’s true what you say about changing direction, like in the Assen chicane – that’s bad as well. It falls in nicely, but then it’s unbelievably heavy to pull it up and flip it over on t’other side. The ’95 bike were much nicer, and that’s why I wanted to try it again, even with the smaller motor and less power – but we never did.” How very Japanese: older is never better, there – but this was an Italian bike!

It speaks volumes for Foggy’s phenomenal grinta, his against-all-odds determination to overcome adversity and win races in the toughest, most competitive class of road racing back then, despite having to cope with such inherent problems with the bike. No wonder they loved Carlo in Italy – he was the two-wheeled equivalent of Nigel Mansell when he drove for Ferrari: Il Leone Inglese – the English lion. But red mist racing of this calibre is hard to maintain over a full 24-race season without making unforced errors, and it was probably inevitable that sooner or later even a rider with an almost accident-free record over the previous three seasons would succumb to the pressure, and start crashing.

“It speaks volumes for Foggy’s phenomenal grinta, his against-all-odds determination to overcome adversity”…

It’s a bit of a miracle Foggy led the ‘97 points table as long as he did, really – especially with Honda’s new supremacy in engine performance. “We were OK on fast tracks with long straights, like Hockenheim,” said Carl, “because there wasn’t hardly anything between us on top speed – our bike’s definitely faster than in ’95. But anywhere else, where acceleration counted more, we were getting left behind – as soon as I got anywhere near, by cornering faster, they’d just get on the gas on the way out of the turn, and motor away from me. Very frustrating.”

“The larger throttle bodies did their job by delivering the biggest horsepower hike the Ducati Superbike had yet enjoyed year-on-year”…

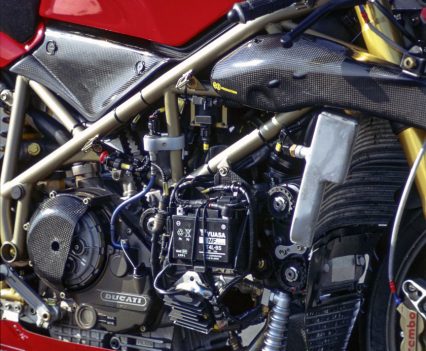

Well, yes – but what happened here was arguably of Ducati’s own making. Unable to increase capacity from ’96 to ’97 in order to counter the growing threat from Honda, the Italian engineers went for more power at almost any cost, in conjunction with improving reliability: Troy Corser’s Promotor Ducati team blew more than 20 engines in 1996, en route to the World title he so nearly lost through mechanical failures – though Troy’s eagerness to rev the motor as high as 12,800 rpm in those pre-limiter days can’t have helped: the 1997 limit was fixed at 12,500 rpm, confirmed by my Assen outing on both bikes. That resulted from a revised 98 x 66 mm 996cc engine with new engine castings and other modifications, homologated like the chassis via the 916SPS street replica.

Those mods included new cylinders with wider-spaced studs and a thicker alloy sleeve (still chrome-plated, as before) to stop them cracking, as often happened in ’96; stronger, heat-treated crankcases; new cylinder heads with bigger inlet ports, revised combustion chambers and on occasion larger valves, matched by a bigger sealed airbox with larger diameter airducts, in turn necessitating a slightly wider fuel tank; closed-up ratios in the six-speed gearbox, reflecting the peakier power curve; a revised exhaust system; bigger oil and water radiators, to cope with the heat generated by the extra power; and most important of all, a new pair of jumbo 60mm throttle bodies for the Weber/Marelli EFI, up from 54mm the previous year, and just 50mm in ’95.

Together with other corresponding modifications, the larger throttle bodies did their job by delivering the biggest horsepower hike the Ducati Superbike had yet enjoyed year-on-year. This meant an 8 bhp increase all the way through the power curve over 1996, delivering 155 bhp at the rear wheel at 12,200 rpm, measured according to Ducati’s ISO method – or about 168 bhp at the gearbox by the more conventional yardsticks other manufacturers used. That was still some way down on Honda’s ‘plus-180 bhp’ gearbox mark for the title-winning RC45, but the V-twin’s narrow girth and wider spread of solid power made up the difference – except for the way in which that power was delivered.

“Imagine sticking a 60mm carburettor on a 500cc single: you’d never get the thing to run at anything less than max revs on full throttle”…

Think about it. Imagine sticking a 60mm carburettor on a 500cc single: you’d never get the thing to run at anything less than max revs on full throttle. Well, thanks to the wonders of the electronic era, Ducati’s clever engineers had managed to programme their dual-injector EFI to let them throw more fuel mixture at each of their cylinders than anyone had yet managed in the history of two-wheeled road racing – and they’d been rewarded by that dramatic increase in outright power. Except, there was a payoff – as I discovered first-hand at Assen, and Foggy & Co. were struggling to cope with all season long: throttle response. That lovely, liquid low-down pickup and midrange torque that had been a trademark of every Ducati V-twin racer so far, had been traded for an on/off switch power delivery, coupled with a massive increase in torque.

While this surely delivered the numbers on the dyno chart, and allowed the V-twin to stay with the Honda V4 on top end performance, it certainly came at the cost of rideability – especially when combined with the light-action but relatively imprecise butterfly throttle, which delivered brutal bottom end response. “I used to be able to lap Albacete practically all in the same gear,” said Foggy, “but now there’s much narrower usable power, you’re having to change gear all the time, and it’s also not the strong, progressive power delivery there used to be.”

Well, OK, maybe you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs – but if the handling suffered into the bargain, then perhaps it wasn’t worth it. How about Frankie Chili’s bike: presumably that had the same personality defects? Hop from one to the other – and immediately I noticed how the Gatalone bike of Superbike racing’s Mr.Nice Guy had a much tighter, together riding position, with a more rational handlebar-to-seat-to-footrest ratio, and the ‘bars tucked in closer compared to Carl’s wider-spread ones. Even though I’m taller than both riders, I instantly felt a part of Chili’s bike whereas I was more perched on top of Carl’s – but that surely reflected their contrasting riding styles. Frankie always used his 125/250GP heritage to stay tucked in, to carry more turn speed for a smoother, more flowing style, whereas Foggy was fiercer and more aggressive with the bike, braking harder and turning more sharply – hence the leverage from the wider ‘bars.

But much to my surprise, this contrast was translated to on-track manners. For a start, the Chili bike definitely didn’t accelerate so brutally, and it was also much smoother off the bottom end. So you could crack the throttle wide open exiting the Assen chicane at 6,000 revs, and feel it pick up strongly and progressively, flattening out the power curve at around 12,000 rpm – more like the ’96 bike, in fact: fabulously fast, but more controllable. Nice! Not only was it not so aggressive in terms of power delivery, there wasn’t the same rush of revs as on Foggy’s bike. It all felt more measured and rideable – but the real surprise was the handling. Apart from one lap exiting the flat-out fifth-gear S-bend behind the pits, where I briefly said hello again to the shimmy-shimmy shake, the Chili Ducati was stable and predictable in its steering, and certainly moved about less than the Fogarty bike had done.

“The Chili bike definitely didn’t accelerate so brutally, and it was also much smoother off the bottom end”…

I found I could hit the gas harder cranked over, without panicking about traction, because of the less abrupt pickup – but it still paid to pull the Gatalone bike fairly upright to use the fat part of the tyre before winding it wide open, because there was still pretty awesome midrange torque, and you could feel the rear Michelin start to spin up, otherwise. That was reasonably easy to do, mostly by using your body weight, but flip-flopping from side to side in the chicane was still hard work, same as on Carl’s, and it definitely seemed harder to lay it into a turn than the Fogarty bike. But the Chili Ducati’s big advantage was the way it held a line better – a crucial factor in Assen’s banked, sweeping bends, where keeping up corner speed is so critical.

“It definitely seemed harder to lay it into a turn than the Fogarty bike. But the Chili Ducati’s big advantage was the way it held a line better”…

Back at base after a much more enjoyable further 20 laps, time to learn some trade secrets. This felt like a different motorcycle: less potent, perhaps, than Foggy’s, which seemed to have less engine inertia, and to pick up revs faster – but definitely better-handling and more refined in feel, adding up to a better package. This was confirmed by my lapping a whole two seconds faster on the Gatalone Ducati than on Carl’s bike. How come? Well, engine first, and it turned out that after Round 6 at Laguna Seca, Frankie complained so vociferously about the Ducati’s power delivery and throttle response – in Italian, of course, which maybe helped! – that the factory engineers cooked him up a new EPROM chip for the next round at Brands.

“I found I could hit the gas harder cranked over, without panicking about traction, because of the less abrupt pickup”…

This began making power 1,000 revs lower, was less aggressive in its delivery and rode the torque curve to increase revs in a more measured way. Result: first time out with the new chip, Frankie won Race 1 at twisty Brands on a track he didn’t much care for, and, er – could well have doubled up if Foggy hadn’t taken him out in Race 2, for which the Brit was properly remorseful, it must be said – but still: the first rule of racing is to beat your teammate, but the second rule is that you must ensure you both stay upright in doing so.

The Chilli bike was much more rideable than the Fogarty machine, in fact AC lapped 2-seconds faster on it.

So I guess the new setup worked, then? “Yes – the engine feels less powerful, but in fact it’s stronger, because you’re staying longer in the true zone of coppia (torque),” Frankie told me at Brands. “Also, it pays to change gear at about 11,800 rpm instead of letting it rev right out, to keep in the strong part of the engine.” One reason for this may be that Fogarty’s motor apparently ran bellmouths that were 30mm shorter than those on Chili’s bike, and Ducati engineers insisted that, contrary to normal expectations, the shorter intake stacks improved bottom end and midrange power, as well as top end, where you’d expect the longer ones to suffer. OK, Frankie – what about the chassis: how come your bike’s so stable compared to Carl’s?

Frankie ran the 1995 triple-clamps off his privateer bike on this 1997 factory bike, which resolved some issues.

“The difference is in the fork yokes [triple-clamps – AC],” admitted Frankie. “Last year I had a ’95 frame because we were a private team, so I try the new 1997 chassis for the first time in Phillip Island, and in the first turn it starts bouncing the front end. So I fit the ’95 yokes off my old chassis, and the handling is much better, so I keep them all season. We still have a problem with the rear suspension, which is either the linkage, or else the shock cannot react to so much bottom power – I think probably the power is too strong. But Corser and I have similar riding styles, so I think for next year we will build on this setting, and try to make the power delivery smoother, like before. But Ducati know what to do – I’m sure they will fix it.” That ’97 frame’s stronger construction meant it was 1.5kg heavier, more robust and stiffer than before (which meant that engine bolts stopped breaking), plus the lighter cast magnesium swingarm threw 2kg more weight bias on to the front wheel – weight distribution was now 53/47%, not bad for a 90° ‘L-twin’.

“The narrower triple-clamps were not only responsible for making the bike feel more compact, they also delivered improved stability in fast, sweeping bends”…

Further investigation uncovered the fact that the ’95 triple-clamps Frankie favoured were 25mm (one inch) narrower than the later ones, which had been spaced out that much to allow the cast stainless brake discs (1mm thicker for ’97) to sit further out in the slipstream, so that they were cooled better. Ever since carbon discs were banned in Superbike racing, heat build-up had been a factor, hence Brembo’s plea for Ducati to stick each disc 12.5mm further out In The Wind.

Perhaps now we can figure out why Frankie kept suffering brake problems that season – as Simon Crafar (Zeltweg) and Neil Hodgson (Sentul) would confirm, after he T-boned them both in turns! The narrower triple-clamps were not only responsible for making the bike feel more compact, they also delivered improved stability in fast, sweeping bends – like at Assen, said Gatalone chief engineer Max Zani, but the downside then was they were only available in two fixed offsets, 30.5mm and 27.5mm, the latter as used by Chili at Assen and delivering a whopping 108mm of trail.

“I must say his bike braked better for me at Assen than Foggy’s, because it didn’t move about so much under braking”…

This is why the bike was much harder to change direction with in a chicane or S-bend, as well as laying into a turn, especially when combined with the wider 24.5° head angle Frankie always used for added stability under braking – even with a 2mm higher rear ride height to try to compensate. I must say his bike braked better for me at Assen than Foggy’s, because it didn’t move about so much under braking at the end of the back straight or stopping for the chicane, where I could also use the sprag clutch to max out engine braking for a hard stop. Frankie’s brakes had more initial bite, too, probably because he used bigger calipers with all the pistons the same size, and sintered pads which worked well straight away but tended to fade sooner, whereas Carl preferred pads with a higher carbon content, which did the opposite.

Carl Fogarty had tried the Chili chassis setup and said he didn’t like it, preferring to live with the shakes rather than heavy up the steering so much – although his teammate Neil Hodgson tried it in Sugo, and was at once much faster, probably because his 125GP-derived riding style was similar to Chili’s. But both riders wanted the adjustable offsets of the ’98 triple clamps, which would allow them to fine-tune the chassis geometry, and reduce the trail without sacrificing stability. As well as a whole host of other factors, chief of which was to rediscover the V-twin motor’s legendary flexibility and user-friendly response, for sure that was high on Ducati’s list for winter development in their efforts to regain the title in 1998 – which, of course, they did! So it wasn’t after all the end of an era – just a Honda-sized hiccup in desmo V-twin supremacy…

So let’s not get this out of proportion: thanks to Carl Fogarty’s tenacity and brilliant riding, this flawed motorcycle led the World Superbike championship until just four rounds from the finish – so it couldn’t exactly be a lemon, could it? And Ducati did achieve their reliability goal, with spectacular success: zero engine failures in a race all season, according to Slick Bass. But moreover, the many wet races in 1997 surely helped John Kocinski and Honda – it can’t have been easy for Foggy to race a bike whose aggressive power delivery surely made it a handful to ride in the rain. Still, the composed handling I experienced on Chili’s bike, and the easier power delivery of its revised EPROM chip, showed Ducati had a valid basis on which to work on grabbing the title back from Honda in ’98, and roll back the march of time. As it indeed did, despite a little local disagreement between Frankie and Foggy in Race 1 at Assen. But that’s another story…!

SPECIFICATIONS – 1997 Ducati 996 Superbike

Engine: Liquid-Cooled DOHC 90-degree V-twin four-stroke, four-valves per cylinder, toothed belt desmodromic camshaft drive, 98 x 66mm bore x stroke, 996cc, 12:1 compression ratio, Weber Marelli efi and ems, two injectors and seperate EPROM per cylinder, 2 x 60mm throttle-bodies, dry multiplate slipper clutch (10 steel/9 sintered), six-speed close-ratio gearbox.

Chassis: Chrome-moly tubular steel spaceframe, single-sided cast magnesium swingarm pivoting in both spaceframe and crankcases, 46mm Ohlins inverted forks, Ohlins shock, 23.5º rake and 102mm trail (Fogarty) / 24.5º rake and 108mm trail (Chilli), 1428mm wheelbase, 53/47% weight distribution, twin 320mm stainless-steel Brembo rotors with four-piston Brembo calipers (front), single 200m stainess-steel Brembo rotor with two-piston Brembo caliper (rear), Marchesini wheels 3.50in and 5.75in, 12/61 – 17in and 18/67 – 17in Michelin slicks.

Performance: 168hp@11,300rpm at gearbox, 160kg without fuel tank, with oil and water, top speed 303km/h (Hockenheim 1997). Owner: Ducati Motor SpA.

1997 Ducati 996 Superbike Gallery